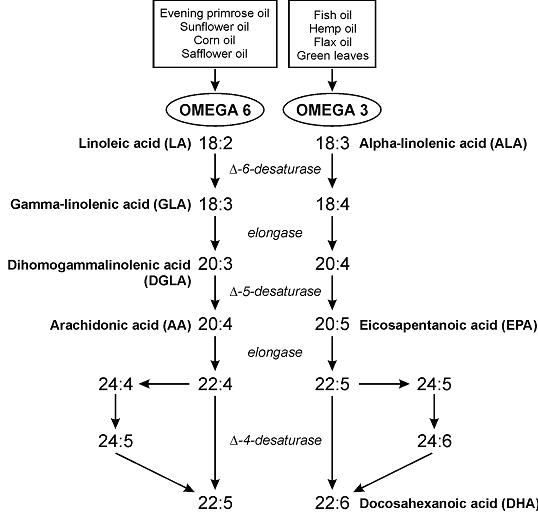

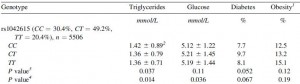

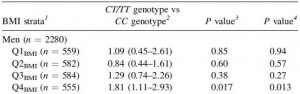

“Desynchronization between the central and peripheral clocks by, for instance, altered timing of food intake, can lead to uncoupling of peripheral clocks from the central pacemaker and is, in humans, related to the development of metabolic disorders, including obesity and type 2 diabetes.”

If you haven’t been following along, a few papers came out recently which dissect this aspect of circadian rhythms — setting the central vs. peripheral clocks.

In brief (1): Central rhythms are set, in part, by a “light-entrainable oscillator (LEO),” located in the brain. In this case, the zeitgeber is LIGHT.

Peripheral rhythms are controlled both by the brain, and the “food-entrainable oscillator (FEO),” which is reflected in just about every tissue in the body – and is differentially regulated in most tissues. In this case, the zeitgeber is FOOD.

In brief (2): Bright light in the morning starts the LEO, and one readout is “dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO),” or melatonin secretion in the evening. Note the importance of timing (bright light *in the morning*) – if bright light occurs later in the day, DLMO is blunted: no bueno.

Morning bright light and breakfast (FEO) kickstart peripheral circadian rhythms, and one readout is diurnal regulation of known circadian genes in the periphery. This happens differently (almost predictably) in different tissues: liver, a tissue which is highly involved in the processing of food, is rapidly entrained by food intake, whereas lung is slower.

Starting the central pacemarker with bright light in the morning but skimping on the peripheral pacemaker by skipping breakfast represents a circadian mismatch: Afternoon Diabetes? Central and peripheral circadian rhythms work together. Bright light and breakfast in the morning.

Continue reading →