Dietary protein “requirements” are some of the most context-dependent nutrient levels to decipher, and depend largely on energy balance and even meal frequency.

An objective look at intermittent fasting (Alan Aragon, 2007)

Meal frequency and energy balance (Lyle McDonald, 2008)

New study: “Increased meal frequency attenuates fat-free mass losses and some markers of health status with a portion-controlled weight loss diet” (Alencar et al., 2015)

This wasn’t well-received in social media because bro-science & many low carb advocates say grazing is no longer in vogue — “it’s much better/healthier/whatever to eat once or twice daily, because intermittent fasting and all that jazz” …however, this may be problematic when it comes to meeting overall protein needs, which is particularly important when you’re losing weight.

The study: 2 vs. 6 meals per day, crossover.

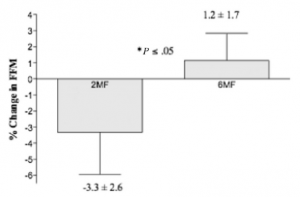

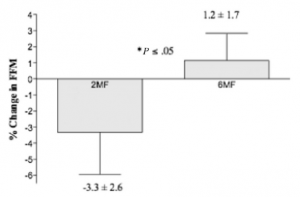

Conclusion: “On average, fat-free mass (FFM) decreased by -3.3% following the 2 meals/d condition and, on average, and increased by 1.2% following the 6 meals/d condition (P<.05).”

In other words, 6 meals per day was better for body composition than 2 meals per day. But context is everything, and this hypothesis has been tested from a variety of different angles, so what does it mean?

The relevant context here: 1) big energy deficit (1200 kcal/d for obese women is a pretty low calorie intake); and 2) “adequateTM” protein intake (75 g/d).

The standard dogma says that in the context of an adequate protein hypocaloric diet, meal frequency matters a LOT, whereas with high protein, it doesn’t matter as much. Theory being that with an “adequate” (read: too low?) overall protein intake, the fasting periods are simply too long with only two meals per day; you need either: 1) higher protein intake; 2) increased meal frequency; or 3) more calories (ie, smaller energy deficit).

In this study, BOTH diets suppressed insulin and induced weight loss, but the increased protein feeding frequency skewed the weight loss to body fat while preserving fat-free mass. I actually agree with a lot of the bro-science in this case, and also think that 75 grams of protein is not enough in the context of a big energy deficit (if body composition is a goal).

Historical precedence?

Meal frequency and weight reduction of young women (Finkelstein et al., 1971)

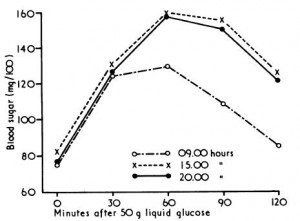

Relevant context: 6 vs. 3 meals per day (3 meals per day may not seem like that many more than 2, but it significantly cuts down on the duration of time spent with no food or protein).

Smaller energy deficit: 1700 kcal/d in overweight patients is less of a deficit than 1200 kcal/d in obese patients.

Higher protein intake: 106 – 115g/d.

Result: nitrogen balance (a surrogate for the maintenance of muscle mass) and fat loss were similar in both groups. This study fixed two problems in the abovementioned study: 1) 3 meals is better than 2 in the context of an energy deficit; and 2) protein intake was higher.

And again here, with 3 vs. 6 meals per day (Cameron et al., 2010), just to make the point that 3 meals per day is better than 2 for preserving lean mass in the context of an energy deficit.

The effect of meal frequency and protein concentration on the composition of the weight lost by obese subjects (Garrow et al., 1981)

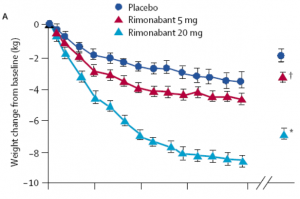

This study tested the opposite extremes: super-low calorie intake (800 kcal/d), much lower protein intakes (20g – 30g/d), and 1 vs. 5 meals per day.

Result: “a diet with a high-protein concentration, fed as frequent small meals, is associated with better preservation of lean tissue than an isoenergetic diet with lower-protein concentration fed as fewer meals.”

It basically confirmed all of the above.

Protein feeding pattern does not affect protein retention in young women (Arnal et al., 2000)

1 vs. 4 meals per day; and 70 grams of protein but no energy deficit (~2000 kcal/d isn’t very hypocaloric for lean young women). In this study, no effect of meal frequency was seen, likely because 70 grams of protein isn’t inadequate when energy intake isn’t restricted.

1. PROTEIN “NEEDS” ARE HIGHLY CONTEXT-DEPENDENT

2. NEED =/= OPTIMIZATION

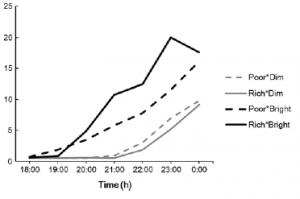

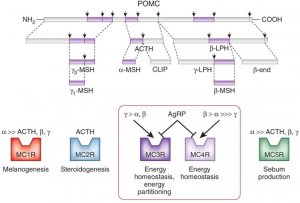

3. MEAL FREQUENCY & meal timing and peripheral circadian clocks > “MACRONUTRIENTS”

If you’re losing weight (ie, in an energy deficit), then intermittent fasting is cool if protein intake is high (above “adequateTM“)… the bigger the energy deficit, the more protein is necessary to optimize changes in body composition.

How much is ‘enough?’ Sorry, can’t give you a gram or even gram per pound of body weight answer… but if you’re losing weight and seeing no discernible effect on body composition (muscle vs. fat mass), then it may be prudent to consider eating more protein-rich foods… and paying more attention to sleep quality (which also greatly impacts nutrient partitioning).

No amount of protein will help you if circadian rhythms aren’t intact!!!

further reading:

Yes, it’s a high protein diet (Tom Naughton, 2015)

Protein requirements, carbs, and nutrient partitioning

Dietary protein, ketosis, and appetite control

Become a Patron!

For personalized health consulting services: drlagakos@gmail.com.

Affiliate links: KetoLogic for keto-friendly shakes, creamers, snacks, etc. And get 15% off your ketone measuring supplies HERE.

Still looking for a pair of hot blue blockers? TrueDark is offering 10% off HERE and Spectra479 is offering 15% off HERE. If you have no idea what I’m talking about, read this then this.

Join Binance and get some cryptoassets or download Honeyminer and get some Bitcoins for free!

20% off some delish stocks and broths from Kettle and Fire HERE.

If you want the benefits of ‘shrooms but don’t like eating them, Real Mushrooms makes great extracts. 10% off with coupon code LAGAKOS. I recommend Lion’s Mane for the brain and Reishi for everything else.

Join Earn.com with this link.

Start your OWN Patreon campaign!

calories proper