I came across a recent study on a mouse model of Angelman Syndrome (an epigenetic disorder), and wasn’t surprised to learn there’s a strong circadian component to it. Epigenetics are one of the main ways circadian rhythms are programmed.

In this case, the circadian connection is more direct.

Angelman Syndrome (AS): you inherit 2 pairs of each gene, one from Mom and one from Dad. In some cases, one of the copies is silenced via epigenetics and you’re basically just hoping the other one is in good shape. In the genetically relevant region in AS, the paternal copy is silenced and the maternal copy does all the heavy lifting, but in AS, the maternal copy is mutated or absent, so none of the genes in this region are expressed.

Interestingly, scientists found that one of the genes, Ube3a (an ubiquitin ligase), is involved in regulating Bmal1, a core circadian gene (Shi et al., 2015) . And mice with a silenced paternal Ube3a and mutant maternal Ube3a exhibit many of the same circadian symptoms of children with AS. They don’t mimic all of the symptoms as there are many other genes in this region. But both show circadian abnormalities.

Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) is the epigenetic opposite: same region of DNA, but silenced maternal copy and mutant or absent paternal copy. This disorder is characterized by massive obesity and low muscle mass (among other things).

While reading about this disorder, I was taken aback with how the obesity was explained.

“Insatiable appetite” (Laurance et al., 1981), although from what I can gather, these children would develop massive obesity even if they were fed cardboard. Some studies even showed no change in food intake and/or energy expenditure (eg, Schoeller et al., 1988), which led some researchers to publish entire papers about how these children must be lying and/or stealing food (eg, Page et al., 1983) .

Further, other researchers even explained their obesity was due to an inability to vomit (Butler et al., 2007).

THEY’RE OBESE BECAUSE THEY’RE NOT BULEMIC.

AYFKM?

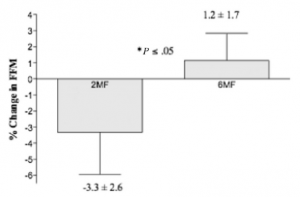

When these kids gain weight, it’s nearly all fat mass; when they lose weight, it’s nearly all muscle [shoulda been a BIG hint]… this even led some researchers (who detected no change in fat mass after significant weight loss) to conclude that their techniques to assess body composition must not be valid in this population because: surely, they must’ve lost some fat mass like normal people do.

THEY FAILED TO CONSIDER THIS IS AN EXTREME CIRCADIAN MISMATCH DISORDER IN NUTRIENT PARTITIONING

It was actually painful to read: these kids are being accused of stealing food and not vomiting because that’s the only way to explain it.

NO IT’S NOT, SCIENCE.

They can be forced into losing fat while maintaining some muscle with an extreme protein-sparing modified fast (eg, Bistrian et al., 1977)…

A few research groups have considered the possibility it’s a hormonal disorder, and some fairly long-term studies with GH replacement have shown promising results (eg, Carrel et al., 1999).

Some have even speculated involvement of leptin (eg, Cento et al., 1999), although this hasn’t been followed-up on.

Disclaimer: I don’t know the cure or best treatment modality for Prader-Willi, although given the strong circadian component in its sister condition, Angelman’s Syndrome, I strongly believe this avenue should be explored (in combination with the seemingly necessary hormonal corrections, which have been the only successful interventions yet). “Diet” doesn’t work; these kids aren’t obese because they’re stealing food or failing to vomit. Interventions strictly targeting CICO have massively failed this population.

Side note: in the Angelman Syndrome mouse model, *unsilencing* the paternal copy worked… maybe the same could work in PWS (and/or other forms of obesity)…?

Evidence supporting potential circadian-related treatment modalities for PWS:

A Prader-Willi locus IncRNA cloud modulates diurnal genes and energy expenditure (Powell et al., 2013)

Symptoms of Prader-Willi associated with interference in circadian, metabolic genes.

Magel2, a Prader-Willi syndrome candidate gene, modulates the activities of circadian rhythm proteins in cultured cells (Devos et al., 2011)

Circadian fluctuation of plasma melatonin in Prader-Willi’s syndrome and obesity (Willig et al., 1986)

And the connection with LIGHT:

Artificial light at night: melatonin as a mediator between the environment and the epigenome (Haim and Zubidat, 2015)

Circadian behavior is light re-programmed by plastic DNA methylation (Azzi et al., 2014)

PWS is much worse than just nutrient partitioning (seriously, just spend a few minutes on any Prader-Willi support forum or this; maybe it is an appetite disorder, but given the data on weight gain [mostly fat mass] and weight loss [mostly muscle mass], it seems far more likely a circadian disorder of nutrient partitioning),

but that component jumped out at me; more specifically, despite the only positive results coming from non-dietary interventions, researchers were still all “#CICO.”

“Lean meat, sugar-free Jello, and skim milk”

FFS

Circadian biology, hormone replacement [where appropriate], and figure out if any specific diets help. PMSF/CR doesn’t work unless “refrigerators and cabinet pantries are locked shut.”

Maybe this applies to other forms of obesity, too.

Maybe.

For personalized health consulting services: drlagakos@gmail.com.

Check out my Patreon campaign! Join the community of over 300 members for up-to-date information about a variety of topics in the health & optimizing wellness space. At 5 bucks a month, can’t beat it!

Affiliate links: KetoLogic for keto-friendly shakes, creamers, snacks, etc. And get 15% off your ketone measuring supplies HERE.

Still looking for a pair of hot blue blockers? TrueDark is offering 10% off HERE and Spectra479 is offering 15% off HERE. If you have no idea what I’m talking about, read this then this.

Join Binance and get some cryptoassets or download Honeyminer and get some Bitcoins for free!

20% off some delish stocks and broths from Kettle and Fire HERE.

If you want the benefits of ‘shrooms but don’t like eating them, Real Mushrooms makes great extracts. 10% off with coupon code LAGAKOS. I recommend Lion’s Mane for the brain and Reishi for everything else.

Join Earn.com with this link.