The glycemic index (GI) ranks foods based on how high 100 grams (~3.5 oz.) of them make go your blood sugar. Dietary simple sugars like sucrose (table sugar) and glucose (e.g., Gatorade) have high GI’s because they are quickly digested and absorbed. Fats and proteins register low on the GI because, well, they don’t provide any glucose. Complex carbohydrates and fibres are intermediate. And most important, mixed meals have a low to intermediate GI. It was once dogma that only high GI foods caused weight gain, but a plethora of somewhat disappointing studies have shown that 1) a low GI diet doesn’t protect lean people from weight gain, and 2) switching from a high to a low GI diet doesn’t facilitate weight loss. Glycemic load (GL) was then introduced which incorporates the amount of the food consumed, such that low GI foods could have a high GL if enough was eaten at once. This fared slightly better than GI, but in the end, the total amount of carbohydrates turned out to be more important than the type of carbohydrates. IOW, WRT glycemia and body weight, quantity outweighs quality. But that doesn’t stop the researchers from testing it … over and over again (on the taxpayers dime!). In their defense, epidemiological studies have demonstrated a very modest relationship between GI/GL and disease risk, just not with body weight, adiposity, etc.

For example,

Substituting white rice with brown rice for 16 weeks does not substantially affect metabolic risk factors in middle-aged Chinese men and women with diabetes or a high risk for diabetes (Zhang et al., 2011 Journal of Nutrition)

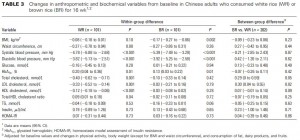

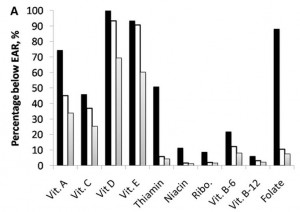

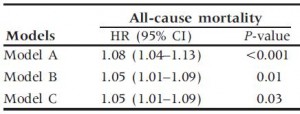

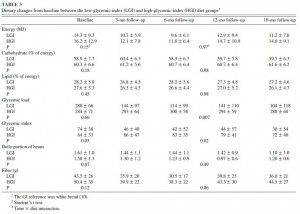

I like this study for its practicality. It is a real-life, highly “do-able” intervention, which is usually a critical concept in interpreting and applying the results from dietary intervention studies. Switching out white rice for brown rice, easy enough! The entire population was Chinese, who ingest phenomenal amounts of rice anyway (>30% of total calories… daily!), so attrition was not a problem. And as wonderfully illustrated in the chart below, making the switch for 4 months had no effect whatsoever (see the P-values in the far right column).

LDL cholesterol went down slightly more in the white rice group, but this is biologically insignificant. All other metabolic parameters were unchanged. For those who like to nit-pick, BMI went down slightly more in the brown rice group while waist circumference went down slightly more in the white rice group, meaning that body composition may have been more favorably affected by white rice :/

This study is reminiscent of a much larger and more important one by none other than Willett and his Harvard cronies in a population of Brazilian women:

An 18-mo randomized trial of a low-glycemic-index diet and weight change in Brazilian women (Sichieri, Hu, Willett et al., 2001 AJCN)

This study was of a similar design; although they targeted both GI and GL. The intervention was more robust; there were much bigger dietary differences between the groups, probably because Willet’s crew has virtually unlimited resources, but this didn’t change the outcome. Total carbohydrate (60% of kcal), fat (27%), and protein (13%) intakes were the same but GI and GL were almost 3 times greater in the high GI (HGI) group compared to the low GI (LGI) group. FTR, “3 times” is a really big difference… IOW, if GI or GL had any effect whatsoever, they would have detected it from a mile away.

For those who were wondering what exactly comprises a low or high GI diet, a sample menu was provided:

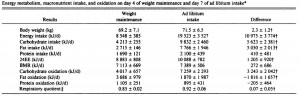

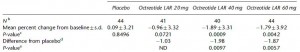

As seen in the table below, there were no dietary differences other than GI & GL between the groups (meaning it was a well-controlled intervention; kudos):

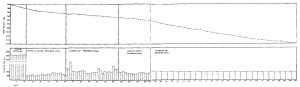

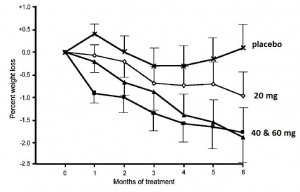

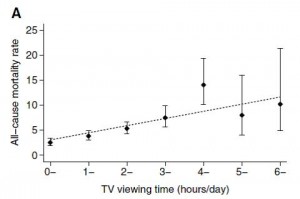

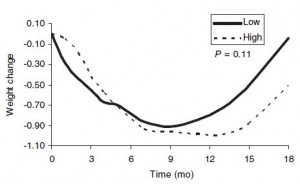

And as illustrated in the figure below, GI and GL had no effect on body weight:

N.B. the scale of the abscissa- it encompasses one kilogram (2.2 pounds); thus, it should look more like this:![]()

Anyway, it looks like both groups lost a LOT of weight, but really their body weight declined very slightly by about 1-2 pounds, then slowly creeped back up (over the course of 18 months). AND for those nit-pickers, it looks like the low GI group ended up slightly heavier! (not really, as the difference was very small and statistically insignificant). IMHO, WRT GI & GL, the Willet study is compelling. It was of the highest quality study design: a randomized, controlled, intervention (as opposed to less conclusive or meaningful epidemiological, observational, cross-sectional, etc., studies). So what was the rationale to re-test GI & GL in a much smaller study with a weaker intervention (brown vs. white rice)? Beats me! But the notion that a low GI or GL favorably affects body weight will not go away. Carbohydrate quantity not quality is the major determining factor.

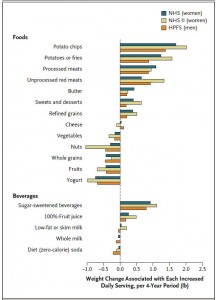

AND as blogged extensively on HERE, potato chips were the most obesogenic foods in one hyooge study. potato chips have a relatively low GI, around 55.

calories proper