the correlation between time spent watching TV and body weight may have nothing to do with the common thought that if kids aren’t watching TV, they’re out playing. No, it turns out that kids who watch less TV eat healthier. They sit around just as much … just not watching TV. Is there something about mindless sitcoms and cartoons that make us want to eat junk food … or snack … wait a minute … subliminal commercial advertising?

Is any of this true? probably not. But if I were to test it, I’d like an intervention study with a couple randomized groups including: one whose TV commercials were strategically replaced with equally fun commercials that don’t promote snack foods; a group of kids who don’t watch TV; and maybe a group who doesn’t watch TV but is exposed to subliminal snack-promoting advertisements… food for thought.

Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men (Mozaffarian, Hao, Rimm, Willett, and Hu, 2011 NEJM)

This is one of the biggest and longest running prospective studies on diet and lifestyle behaviors. That’s not to say it’s the best study; epidemiological, observational, and prospective studies are subject to a variety of crippling limitations; but this one is big.

It is a compilation of three big studies that I’ve blogged about in the past:

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS, n=121,701, est. 1976)

The Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS II, n=116,686, est. 1989)

The Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS, n=51,529, est. 1986)

All in all, a total of 1,570,808 person-years were analyzed (person-years: 16 people x 2 years = 32 person-years). The biggest finding? everybody gains weight, about 0.835 pounds per year. It doesn’t sound like much but after 20 years it means you’re 15 pounds fatter.

The second biggest finding? Drumroll please…

First, to set the mood: people don’t gain weight magically. This study was unique in that there were multiple dietary assessments, performed over a very long period of time, in the same group of people. And one way people gain weight is by eating more. So these authors were able to see which foods, when increased in the diet, correlated with weight gain.

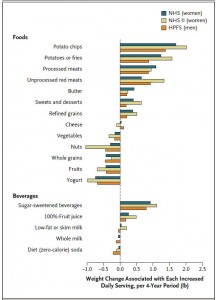

And the winner was, somewhat surprisingly, potatoes! Actually number 1 was potato chips, and number 2 was potatoes and French fries or crisps. The surprise, IMHO, was that soda and junk food was much further down the list. Furthermore, I might have thought potato chips could be number 1 because of their high trans-fat content, but the presence of potatoes (which lack trans-fats) at number 2 means that trans-fats are not the obesogenic component of potato chips.

The figure (kudos for data presentation):

To quote the study [sic]: “Strong positive associations with weight change were seen for starches, refined grains, and processed foods.” WRT study design, such conclusions cannot be interpreted to mean: eating less “starches, refined grains, and processed foods” will prevent weight gain. It means body weight was determined by changes in the amount of “starches, refined grains, and processed foods” were in the diet… if any of those foods were increased, body weight increased; and if any of those foods decreased, body weight decreased. (note: this study was not designed to determine causation).

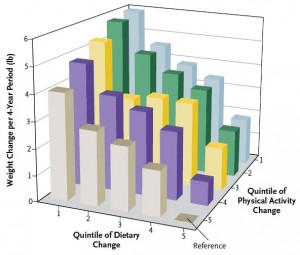

Exercise was also included in their analysis. Another good-looking figure, albeit a little more complicated:

Think of the bottom left (front?) as the sum of good dietary changes (associated with weight loss [or less weight gain]). People in the first “Quintile of Dietary Change” increased their consumption of “starches, refined grains, and processed foods” and gained the most weight, while those in the fifth quintile ate less and lost weight or stayed the same. A similar trend for physical activity is displayed on the bottom right part of the figure. People in the first quintile increased their physical activity, while those in the fifth quintile reduced their physical activity. If you compare the amount of weight gain from the fifth to the first quintiles of dietary change (all the purple bars, for example), the amount of weight gained is highly dependent on diet. However, within any given quintile of dietary change, not much weight is gained or lost by changing the amount of exercise (follow any set of bars from gray to purple to yellow to green to blue). IOW, at any given quintile of physical activity change, diet predicts much larger changes in body weight. Heck, people in the second quintile of dietary change actually gained weight by increasing physical activity … that’s a bit convoluted, but it demonstrates the case that in this enormous data set, diet was a better predictor of weight gain than physical activity (which in some cases didn’t matter at all).

Eat less and move more?

Calories proper