There is no longer a debate on the value of protein supplements for exercisers. Now I’d like to make the case for protein timing, or more specifically the value of pre-workout protein supplementation.

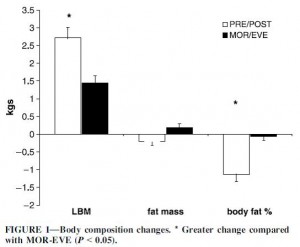

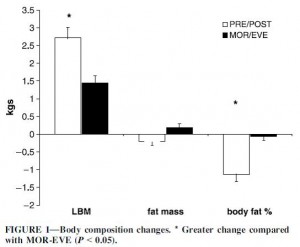

Cribb and Hayes (2006) examined the two extremes of protein consumption: immediately before and after working out (“PRE-POST”) vs. 8 hours before and 8 hours after working out (early morning and late evening; “MOR-EVE”). Each protein shake contained 40 grams protein, 43 grams glucose, and 7 grams creatine. The subjects were recreational weight lifters, an interesting choice in terms of data interpretation. I.e., novices are expected to see much greater gains from beginning a new exercise program than experienced exercisers. Thus, any difference between the groups is expected to be greater. For example: compare the difference between 5 and 10 to that of 1 and 2. The relative difference (2x) is the same in both cases, but the absolute difference between 5 and 10 is significantly greater and thus easier to detect. This stacked the odds against seeing a difference between treatments. The advantage is that experienced lifters know how to do a high intensity workout, and the results are applicable to people who already exercise.

Notes on the wonders of energy balance:

The protein shakes added ~272 kcal to their total food intake, which caused them to eat less during the rest of the day. Interestingly, food intake declined by 74 kcal in the PRE-POST group and over twice as much (172 kcal) in MOR-EVE. Food intake declined in MOR-EVE because the extra calories were just floating around in the bloodstream and thus available to register lots of “excess energy” to the brain. But the increase in muscle was 2x greater in PRE-POST than MOR-EVE; thus, the extra calories in PRE-POST were immediately invested in laying down new lean mass and therefore weren’t around to signal “excess energy” to the brain.

energy in energy out is bollocks

How the “energy in” is handled is critically important. With regard to an energy excess, dessert before bedtime is stored as fat but the same amount of calories from protein before exercise are invested into muscle.

A calorie isn’t a calorie because body composition matters.

Continue reading →