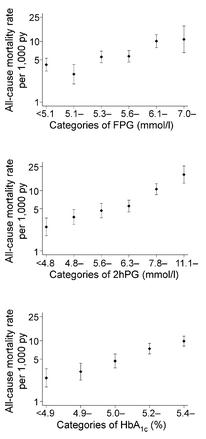

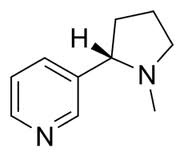

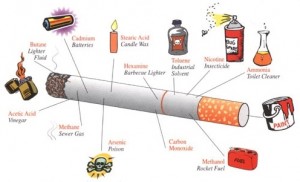

Or more specifically, caffeine and nicotine… or really just nicotine. Today is about the lesser of two evils: nicotine, Mother Nature’s little helper (the other evil being cigarettes [not coffee]). This curious little molecule is an anti-inflammatory memory boosting appetite suppressant. If it didn’t screw with the reward mechanisms in your brain, it’d be a vitamin.  Part 1. Cigarettes, nicotine, and metabolic function

Part 1. Cigarettes, nicotine, and metabolic function  Exhibit A: Activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway ameliorates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance (Wang et al., 2011) translation: “nicotine is good for mice.” Continue reading

Exhibit A: Activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway ameliorates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance (Wang et al., 2011) translation: “nicotine is good for mice.” Continue reading

awesome finder

-

Recent Posts

- Would you like your next meal to be your last… in a really long time??

- Health “Biohacks”

- Most sleep drugs are absolute shit.

- Hey GLP-1 nerds, check out Nesfatin-1

- The All New “Uh-Oh CIM”

- 5x greater intake of seed oils. Place your bets!?

- Rebranding GLP-1Ra & SGLT2i as “CIM” O_o

- Seed oils.

- This mouse-alcohol-energy balance study is breaking the internet.

- Canagliflozin, semaglutide, and tirzepatide OH MY

- Homemade Healthy Hot Mustard. Recipe.

- B&M, Bimagrumab and Miragrebon. Get your grubz on.

- Tirzepa-what now??

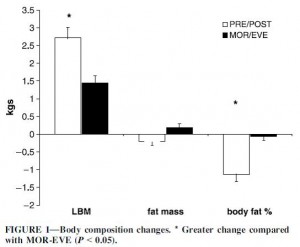

- #eTRF 2022

- Death cycles of bodybuilders

-

Twitter live feed

-

-