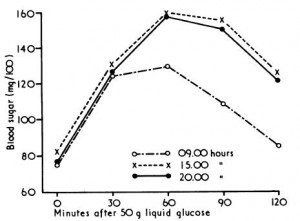

Meal & exercise timing in the contexts of “damage control” and nutrient partitioning are frequent topics on this blog. I generally opt for a pre-workout meal, but nutrient timing hasn’t panned out very well in the literature. That’s probably why I’m open to the idea of resistance exercise in the fasted state. A lot of pseudoscientific arguments can be made for both fed and fasted exercise, and since a few blog posts have already been dedicated to the former, this one will focus on the latter.

The pseudoscience explanation is something like this: since fatty acids are elevated when fasting, exercise in this condition will burn more fat; and chronically doing so will increase mitochondria #. The lack of dietary carbs might enhance exercise-induced glycogen depletion, which itself would bias more post-workout calories toward glycogen synthesis / supercompensation. Much of this is actually true, but has really only been validated for endurance training (eg, Stannard 2010, Van Proeyen 2011, & Trabelsi 2012; but not here Paoli 2011)… and the few times it’s been studied in the context of resistance exercise, no effect (eg, Moore 2007 & Trabelsi 2013). However, there are some pretty interesting tidbits (beyond the pseudoscience) which suggest how/why it might work, in the right context.

Exercising fasted or fed for fat loss? Influence of food intake on RER and EPOC after a bout of endurance training (Paoli et al., 2011)

John Kiefer, an advocate of resistance exercise in the fasted state, mentioned: “the sympathetic nervous system responds quicker to fasted-exercise. You release adrenaline faster. Your body is more sensitive particularly to the fat burning properties of adrenaline and you get bigger rushes of adrenaline.”

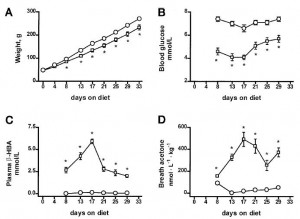

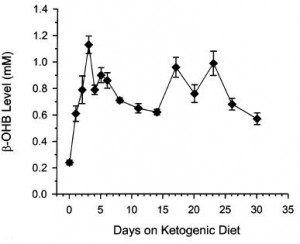

Much of this is spot on. That is, ketogenic dieting and glycogen depletion increase exercise-induced sympathetic activation and fat oxidation (eg, Jansson 1982, Langfort 1996, & Weltan 1998).

The question is: can this improve nutrient partitioning and physical performance? Magic 8-Ball says: “Signs point to yes.” I concur.

Contrary to popular beliefs, glycogen depletion per se doesn’t harm many aspects of physical performance. A lot of fuel systems are at play; you don’t need a full tank of glycogen.

Effect of low-carbohydrate-ketogenic diet on metabolic and hormonal responses to graded exercise in men (Langfort et al., 1996)

High-intensity exercise performance is not impaired by low intramuscular glycogen (Symons & Jacobs, 1989)

Increased fat oxidation compensates for reduced glycogen at lower exercise intensities (eg, Zderic 2004), and ketoadaptation may do the same at higher intensities.

Continue reading →