Figuring out how best to eat, physiological insulin resistance, and an homage to pioneering nutrition research.

Insulin resistance, as we know it today, is associated with poor nutrition, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome. But it’s FAR more interesting than that. Indeed, it could even save your life. At the time when the pioneering studies discussed below were occurring, the researchers had no idea insulin resistance was going to become one of the most important health maladies over the course of the following century. Furthermore, these somewhat-primitive studies also shed some light, possibly, on how we should be eating. hint: it might all come down to physiological insulin resistance.

The reduced sensitivity to insulin of rats and mice fed on a carbohydrate-free, excess fat diet (Bainbridge 1925, Journal of Physiology)

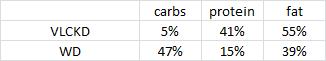

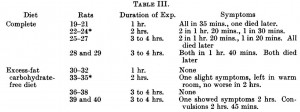

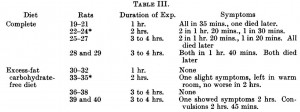

Rats were fed either a normal starch-based diet (low fat), or a high butter diet (low carb) for one month, then fasted overnight and injected with a whopping dose of insulin (4 U/kg). First, take a guess, what do you think happened and why. Then, click on the table below.

To make a long story short, all the starch-fed rats died while all the butter-fed rats lived.

On a high-fat zero-carb diet, plasma insulin levels are low. Insulin is low because there no carbs (i.e., it’s supposed to be low). Under conditions of low insulin, unrestrained adipose tissue lipolysis leads to a mass exodus of fatty acids from adipose tissue. These fatty acids accumulate in skeletal muscle and liver rendering these tissues insulin resistant. But this doesn’t matter, because insulin sensitivity is unnecessary when there aren’t any carbs around. So if that rogue research scientist who’s always trying to jab you with a syringe filled with insulin actually succeeds, you won’t die. The high-fat diet prevents insulin-induced hypoglycemic death. This is physiological and absolutely critical insulin resistance.

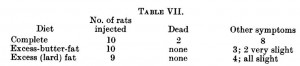

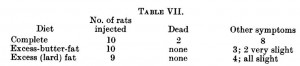

To determine if this was specific to dairy (butter) or a general effect of a high fat zero carb diet, Bainbridge repeated the experiments with lard. Lo-and-behold, lard-fed rats were just as fine as those dining on butter.

To be sure, these studies exhibited a high degree of animal cruelty… but their simplicity is laudable. And Bainbridge’s findings are not an isolated case.

Studies on the metabolism of animals on a carbohydrate-free diet. Variations in the sensitivity towards insulin of different species of animals on carbohydrate-free diets (Hynd and Rotter, 1931)

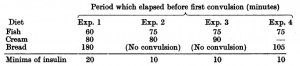

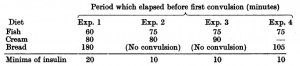

Instead of starch, lard, and butter, Hynd and Rotter used milk and bread, cheese, and casein. And their findings were essentially identical to Bainbridge’s: mice, rats, or rabbits fed carbohydrate-free diets were insulin resistant and protected against insulin-induced tragedies.

The interesting finding was in kittens, who sadly maintained insulin sensitivity when fed fish (high protein) or cream (high fat).

You’re probably thinking: why would I say any state of heightened insulin sensitivity is “sad?” WELL, I say “sad” because we’re talking about physiological insulin resistance; a condition when resistance to the hypoglycemic effect of insulin is essential, and lack thereof is incompatible with survival. To be clear: 1) kittens remain insulin sensitive on high fat and protein diets; and 2) this is OK because there aren’t any rogue research scientists running around trying to jab them with insulin. While I can’t say for sure, this might have something to do with what kittens are supposed to eat, i.e., their natural diet. High protein and fat diets won’t make them insulin resistant because unlike rodents, that is their normal diet. (real mice eat fruits and seeds; laboratory mice eat pelleted rodent chow; cartoon mice eat cheese.) Lard causes ectopic lipid deposition in insulin sensitive tissues in rodents because they aren’t accustomed to it. Mice are optimized to eat a high carb diet. Kittens eat protein and fat, usually in the form of mice. But when given bread, kittens develop insulin resistance. There is no bread in mice.

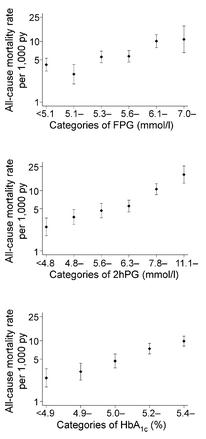

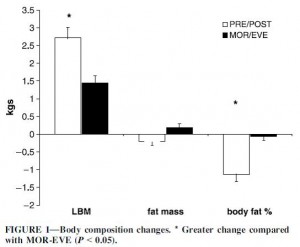

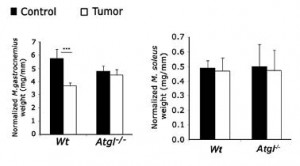

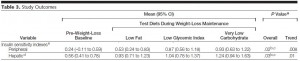

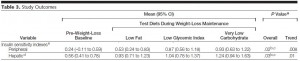

While we shouldn’t base our diet around the possibility of turning a corner and being jabbed with a syringe filled with insulin, perhaps we are simply more similar to kittens. Hypercaloric diets loaded with sugar, excess carbohydrates, and empty calories cause [pathological] insulin resistance (which could theoretically save your life if a rogue research scientist jabbed you with insulin), whereas the opposite is true for diets high in fat and protein. This is repeatedly demonstrated in diet intervention studies, most recently in the notorious Ebbeling study (Missing: 300 kilocalories). When people were assigned to the very low carbohydrate diet, insulin sensitivity was significantly higher than when they were on low fat diets: Soapbox rant: I’m not saying low carb is what we are supposed to eat. Nor am I saying it is the optimal diet. IMHO any diet which excludes processed junk food and empty calories is “healthy.” The Paleo diet isn’t healthy because some nutritionista says it’s what we are supposed to eat; Paleo

Soapbox rant: I’m not saying low carb is what we are supposed to eat. Nor am I saying it is the optimal diet. IMHO any diet which excludes processed junk food and empty calories is “healthy.” The Paleo diet isn’t healthy because some nutritionista says it’s what we are supposed to eat; Paleo is healthy for the same reason as Atkins

is healthy for the same reason as Atkins , Zone

, Zone , South Beach

, South Beach , and a million others: no junk food.

, and a million others: no junk food.

Maybe the diet we’re supposed to eat has nothing to do with the healthiest diet. Maybe not. But it probably isn’t bad for you. just sayin’

calories proper

and Kwasniewski

. On the other hand, 41% protein is pretty high.