and what we can’t learn from rodent studies.

Mandatory pre-reading: Exercise alone won’t cut it

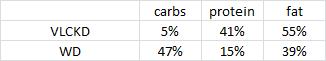

It’s difficult to conduct experiments on energy balance in humans because they’re we’re all so diverse. This is one reason why researchers use animal models; diet, exercise, and even genetic background can be rigorously controlled to a degree unimaginable in humans. Despite all of this, however, exercise studies involving rodents are consistently inconsistent and inherently flawed. They are not applicable to weight loss or energy balance in humans. “Attention nutrition researchers, stop doing them.”

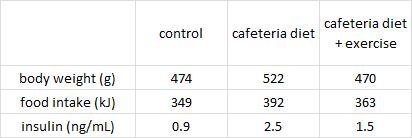

Exhibit A. Cafeteria diet-induced insulin resistance is not associated with decreased insulin signaling or AMPK activity and is alleviated by physical training in rats (Brandt et al., 2010)

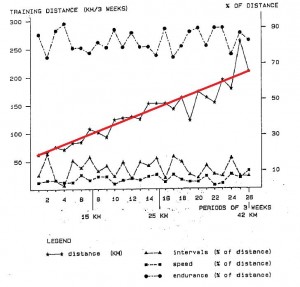

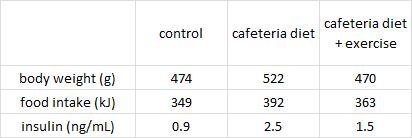

Three groups of rats: 1) chow-fed controls; 2) cafeteria-junk-food-diet; and 3) cafeteria-junk-food-diet + exercise. The exercise was high intensity and consisting of swimming 5x per week with a tiny dumbbell attached to their tail (equal to 2% of their body weight).

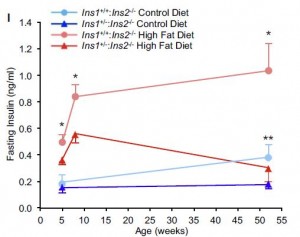

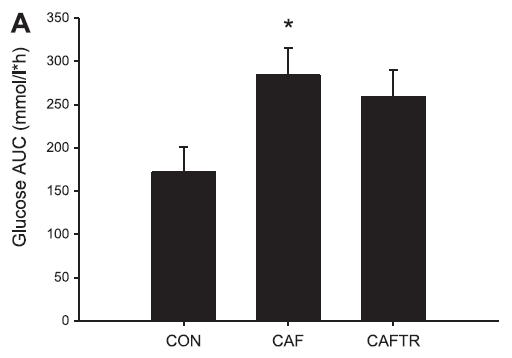

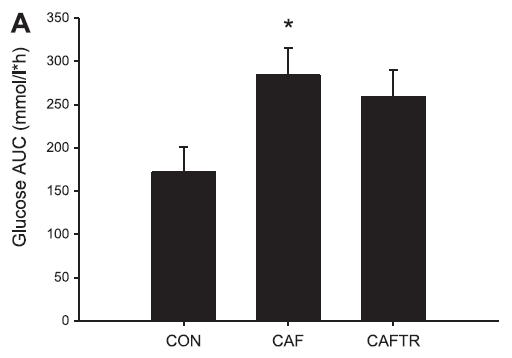

In these lucky rats, exercise completely blunted weight gain, but did so, at least in part, via reduced food intake. Exercise-induced anorexia might reflect the unnatural-ness of a rat subjected to a rigorous exercise protocol; it’s stressful for them. Exercising rats are not happy thinking they’re doing something good for themselves; they’re trying to not drown. And while exercise corrected their body weight, it failed to normalize fasting insulin (above) and glucose tolerance (which may also confirm they are stressed out):

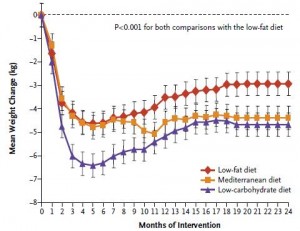

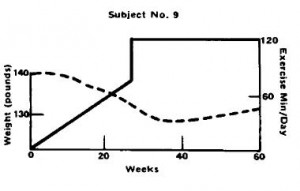

Needless to say, in humans, it’s the exact opposite. With exercise, food intake increases, body weight stays the same (usually), and insulin sensitivity is superbly enhanced. But to further drive home the point that these studies should not be conducted with rodents, it’s not even consistently “the exact opposite.”

Exhibit B. Effects of food pattern change and physical exercise on cafeteria diet-induced obesity in female rats (Goularte et al., 2012)

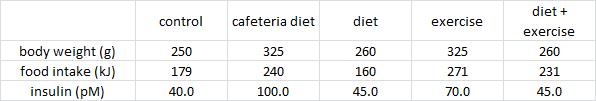

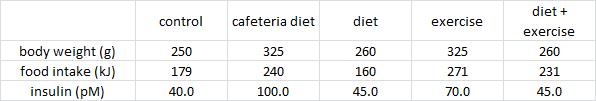

In this somewhat more complicated study, cafeteria diet-fed rats: 1) went on a diet; 2) started an exercise regimen; or 3) both.

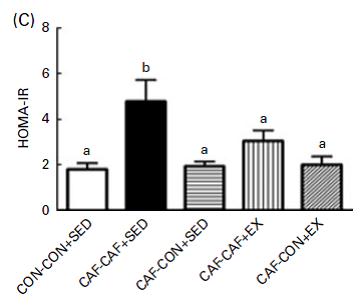

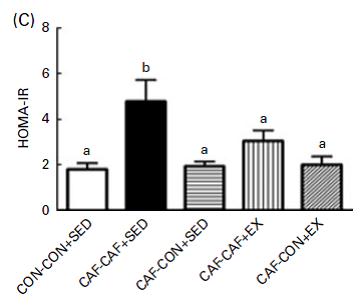

In contrast to Brandt’s findings, exercise increased food intake and failed to reduce body weight (similar to unlucky subject number 9). However, in agreement with Brandt, exercise failed to normalize insulin (above) and glucose tolerance:

One of the greatest metabolic benefits of exercise in humans, i.e., restoration of insulin sensitivity, is not reproduced in 2 rodent studies.

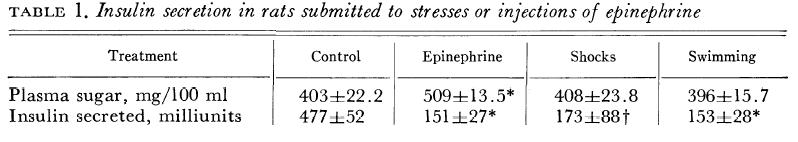

Unfortunately, the hypothesis that exercising rats is just like torturing rats was actually tested.

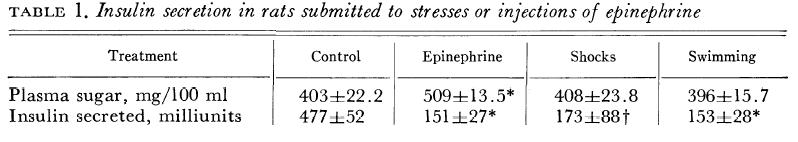

Exhibit C. Effects of epinephrine, stress, and exercise on insulin secretion by the rat (Wright and Malaisse, 1968) Swimming had an effect on glucose and insulin that was strikingly similar to receiving foot shocks (i.e., electrocution).

Swimming had an effect on glucose and insulin that was strikingly similar to receiving foot shocks (i.e., electrocution).

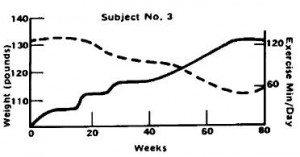

And last but not least, to bring it around full circle, here’s how it is supposed to look:

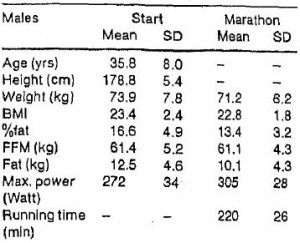

Exhibits D, E, and F. A 12-week aerobic exercise program reduces hepatic fat accumulation and insulin resistance in obese, Hispanic adolescents (van der Heijden et al., 2012)

Exercise protocol: cycling. 10 minutes warm-up, 30 minutes at 70% VO2peak (HR > 140 bpm), 10 minutes cooldown. Only TWICE per week.

1) VO2peak significantly improved, confirming that this seemingly puny exercise routine had a real physiological impact.

2) Neither body weight nor fat mass declined, suggesting this was truly “exercise alone.” I.e., they weren’t dieting.

3) HOMA-IR, a measure of insulin resistance, declined.

1+2+3 = exercise improves insulin sensitivity.

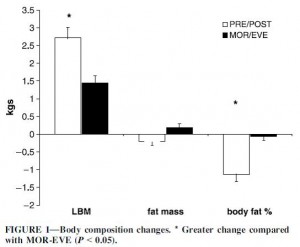

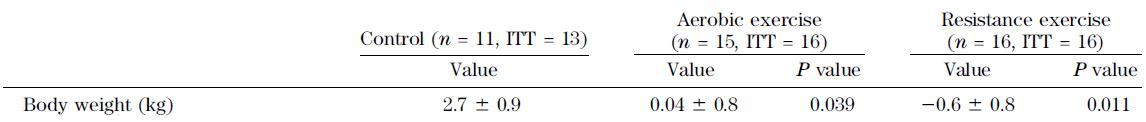

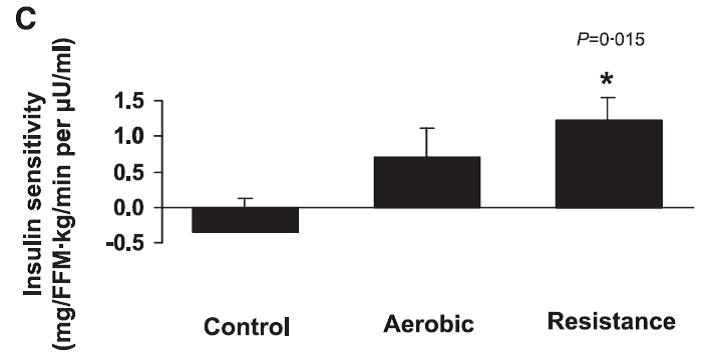

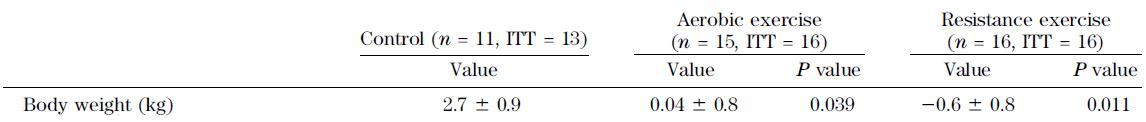

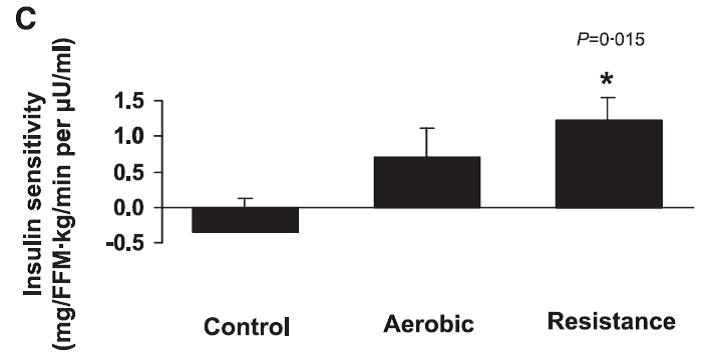

Effects of aerobic versus resistance exercise without caloric restriction on abdominal fat, intrahepatic lipid, and insulin sensitivity in obese adolescent boys (Lee et al., 2012)

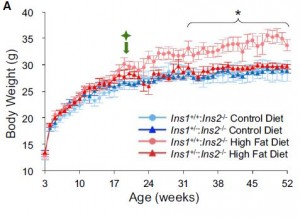

Above: body weight didn’t change, confirming this was “exercise alone.”

Below: insulin sensitivity improved in both exercise groups.

It’s been almost 100 years, why can’t the rats get it right? (by “rats,” I mean scientists who tie weights to rats tails, throw them into a tub of water, and call it “exercise”).

calories proper