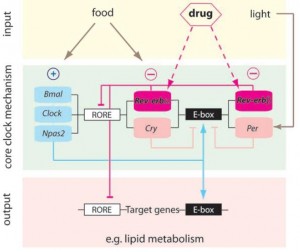

BMAL1 and CLOCK, ‘positive’ regulators of circadian gene expression, activate transcription of the negative regulators Per, Cry, and Rev-erb. PER and CRY inhibit BMAL1 and CLOCK, whereas Rev-erb inhibits Bmal1. It is said that Rev-erb is “an important link between the positive and negative loops of the circadian clock.” You don’t really need to know any of that to follow this blog post.

awesome finder

-

Recent Posts

- Would you like your next meal to be your last… in a really long time??

- Health “Biohacks”

- Most sleep drugs are absolute shit.

- Hey GLP-1 nerds, check out Nesfatin-1

- The All New “Uh-Oh CIM”

- 5x greater intake of seed oils. Place your bets!?

- Rebranding GLP-1Ra & SGLT2i as “CIM” O_o

- Seed oils.

- This mouse-alcohol-energy balance study is breaking the internet.

- Canagliflozin, semaglutide, and tirzepatide OH MY

- Homemade Healthy Hot Mustard. Recipe.

- B&M, Bimagrumab and Miragrebon. Get your grubz on.

- Tirzepa-what now??

- #eTRF 2022

- Death cycles of bodybuilders

-

Twitter live feed

-

-