Gluten is protein, not carbs. A gluten-free diet is frequently low-carb, because most dietary gluten comes in the form of bread (and wheaty foods). But believe it or not, bread is an incredibly complex food… many different proteins, carbohydrates, and nutrients that could be problematic for some people (more on this later).

Gluten is not a FODMAP

is not a FODMAP , but most gluten-containing foods are. Gluten is actually very rich in the amino acid glutamine. Gluten, not bread.

, but most gluten-containing foods are. Gluten is actually very rich in the amino acid glutamine. Gluten, not bread.

So we have three studies on purified “gluten,” asking if it’s the gluten, FODMAPs, or something else in wheaty food that is problematic.

Study #1. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of FODMAPs (Biesiekierski et al., 2013)

Strong study design; patient population was people who thought they were gluten sensitive (but definitely not celiac).

This is the study which led journalists to claim non-celiac gluten sensitivity doesn’t exist, and it’s really sensitivity to FODMAPs, in part, because of this:

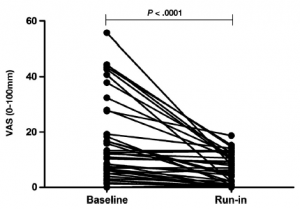

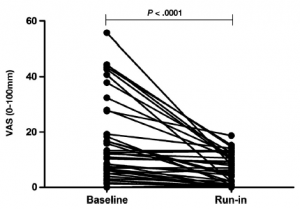

Baseline = low gluten diet

Run-in = low gluten and low FODMAPs

Here’s the fly in the ointment:

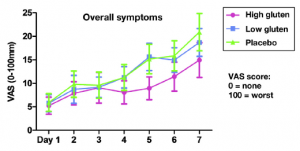

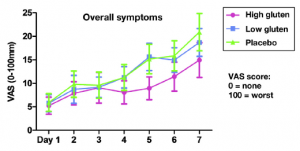

After the run-in period, subjects still followed their gluten-free diets but also received either 16g relatively pure gluten /d (High gluten), 2g gluten + 14g whey protein (Low gluten), or 16g whey protein (placebo). GI symptoms returned in all participants. So, low FODMAPs worked for about a week, but then symptoms returned regardless of whether they were eating gluten or not. In other words, neither low FODMAPs nor low/no gluten worked very well in this study.

/d (High gluten), 2g gluten + 14g whey protein (Low gluten), or 16g whey protein (placebo). GI symptoms returned in all participants. So, low FODMAPs worked for about a week, but then symptoms returned regardless of whether they were eating gluten or not. In other words, neither low FODMAPs nor low/no gluten worked very well in this study.

But this study may have introduced a brilliant new confounder: food intake was strictly controlled — the experimental diets were different from their normal diets. Restricting gluten and FODMAPs may have provided some transient benefit, but if the new experimental diet introduced something else that caused problems, then that may explain the gradual return of symptoms…

bollixed?

Study #2. Small Amounts of Gluten in Subjects with Suspected Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity: a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Trial (Di Sabatino et al., 2015)

It was another high quality study design: “Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over.” And it was addressing a basic question: do people who strongly suspect they have non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) really have NCGS? Alternatively, is NCGS real?

Intervention was strong:

1) 4.375 grams of gluten or placebo (rice starch) daily for a week. This is roughly equivalent to two slices of bread (note: this is way more than enough gluten to destroy the intestines of a patient with bona fide celiac disease).

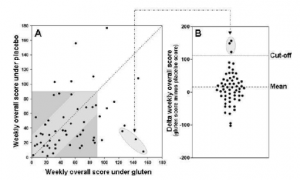

2) important: they defined the what they would classify as NCGS prior to starting the trial. A priori.

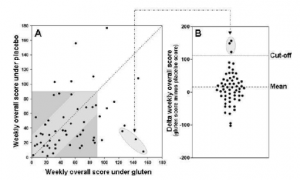

61 patients strongly suspected of NCGS started the trial, and one withdrew due to gluten-related symptoms in both the gluten and placebo groups.

Results: regardless of whether they were assigned to gluten or placebo FIRST (prior to the crossover), most patients reported gluten-related symptoms. More importantly, 3 of the 59 patients exhibited significantly worse symptoms on gluten relative to placebo according to the endpoint they defined prior starting the trial. In one sense, this could be interpreted to mean 5% of people who strongly believe they have NCGS actually have NCGS.

Two patients reacted just as selectively strongly to the placebo as the three “real” NCGS patients did to gluten. Rice-starch sensitivity?

See here for a more detailed description of the statistics involved in this study. I’m willing to accept the “5%” rate, despite the strength of the placebo-responders, whereas the author of that blog post is not. That’s fair, imo.

And here is another article which questions the legitimacy of NCGS based on this study. I don’t think that’s totally fair.

And Raphael’s post, where he humorously concludes: “[Gluten-free] does not include advice to sport a gas mask when walking past bakeries.”

Study #3. Effect of gliadin on permeability of intestinal biopsy explants from celiac disease patients and patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity (Hollon et al., 2015)

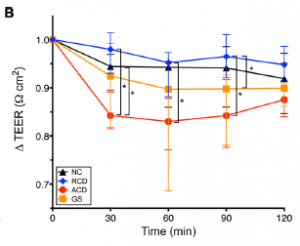

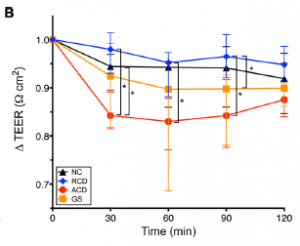

“Delta TEER” is basically the amount of intestinal permeability in intestinal explants exposed to media + gluten (experimental condition) minus those exposed to plain media (control condition). A better control condition, imo, would’ve been something like they did above: substitute gluten with another protein like whey protein.

NC: healthy people

RCD: celiac patients in remission

ACD: celiac patients with active disease

GS: non-celiac gluten sensitivity

Active celiac samples responded significantly worse than those in remission, which is good as it functions as a positive control for the experimental protocol.

However, gluten sensitive samples responded significantly worse than celiac remission samples; actually, they responded just as badly as celiac samples with active disease. Celiac disease is supposed to be a million times worse than non-celiac gluten sensitivity… and statistically speaking, even permeability the normal samples declined as much as NCGS samples.

This led some to conclude that gluten is bad for EVERYONE. I’d say it means the assay is bollixed. Occam’s razor?

My advice: don’t be anti-science, but don’t use bad science to justify diet choices. We simply need better studies on non-celiac gluten sensitivity and FODMAPs.

If bread doesn’t work for you, don’t eat bread. You’re not missing much.

If you like what I do and want to support it, check out my Patreon campaign!

Affiliate links: still looking for a pair of hot blue blockers? Carbonshade and TrueDark are offering 15% off with the coupon code LAGAKOS and Spectra479 is offering 15% off HERE. If you have no idea what I’m talking about, read this then this.

20% off some delish stocks and broths from Kettle and Fire HERE.

If you want the benefits of ‘shrooms but don’t like eating them, Real Mushrooms makes great extracts. 10% off with coupon code LAGAKOS. I recommend Lion’s Mane for the brain and Reishi for everything else.

Join Earn.com with this link. Get paid to answer questions!

calories proper

calories proper

Become a Patron!

Save