or

Weight-loss maintenance, part 1

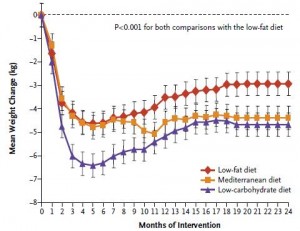

“Weight-loss maintenance” is a critical part in the battle against obesity because losing weight is much easier and significantly more successful than keeping it off. The difference lies predominantly in duration: a few months of dieting to lose weight vs. keeping it off for the rest of your life. Two diet studies on the topic were recently published, and while neither study really addressed the issue proper, some interesting points can be gleaned from both.

Study #1

Meal timing and composition influence ghrelin levels, appetite scores and weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese adults (Jakubowicz et al., 2012)

16 weeks of weight loss followed by 16 weeks of “weight-loss maintenance.”

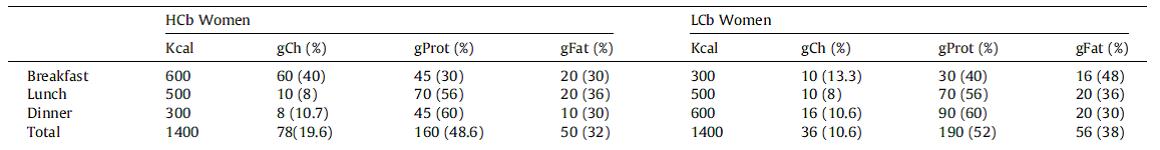

In brief, the weight loss was accomplished by one of two hypocaloric (1400 kcal/d) isocaloric pseudo-Dukan Diets (higher protein & lower fat than Atkins

(higher protein & lower fat than Atkins )

)

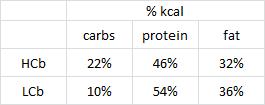

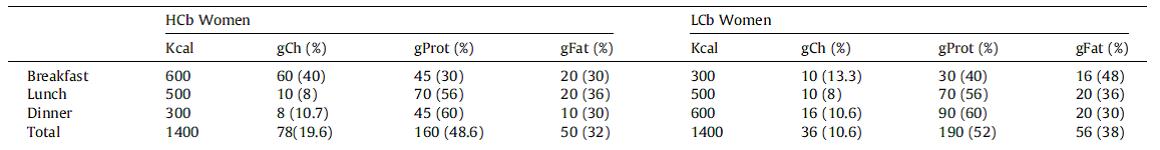

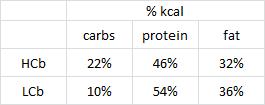

The catch: Breakfast for the people in HCPb (High Carbohydrate and Protein breakfast) had twice the calories, 6x the carbs, and half more protein than LCb (Low Carb breakfast). This was compensated, calorically, by a much smaller dinner. In other words, they ate like a King for breakfast, a Prince for lunch, and a Pauper for dinner… with the added bonus of a “sweet food… chocolate, cookies, cake, ice cream, chocolate mousse or donuts.” For breakfast.

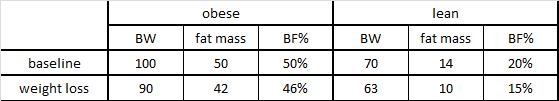

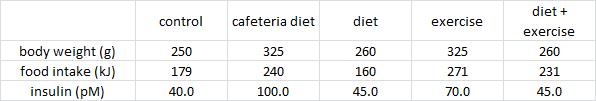

People in both groups lost roughly similar amounts of weight in the weight loss phase:

During the first 16 weeks (weight loss phase), a strict 1400 kcal diet was implemented. During the second 16 weeks (“weight-loss maintenance” phase), macronutrient composition was supposed to be kept similar, but subjects were “free to eat as motivated by hunger or cravings.” Critique #1a: this study would’ve greatly benefitted by food intake questionnaires to know more accurately what these people were eating; the importance of this becomes more apparent soon.

At three times throughout the study (baseline, week 16, and week 32), a “Breakfast meal challenge” was administered to assess Hunger, Hatiety, and Food Cravings. Unfortunately, however, the “Breakfast meal challenge” was administered… after… breakfast. HCPb binged on a high calorie 3-course meal which included dessert while LCb nibbled on a lite breakfast… And the researchers needed a 100-millimeter Visual Analog Scale and 28-item Food Craving Inventory Questionnaire to figure out who would be hungrier afterwords? Really?

Divide and conquer

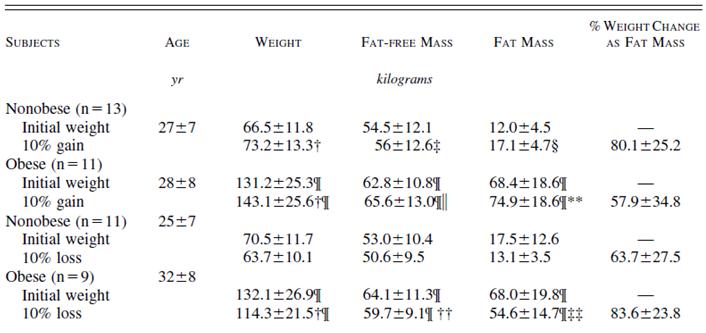

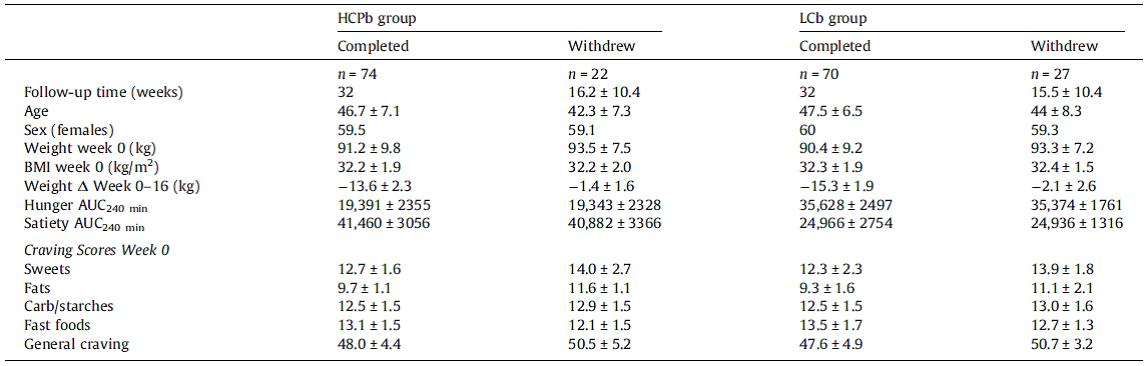

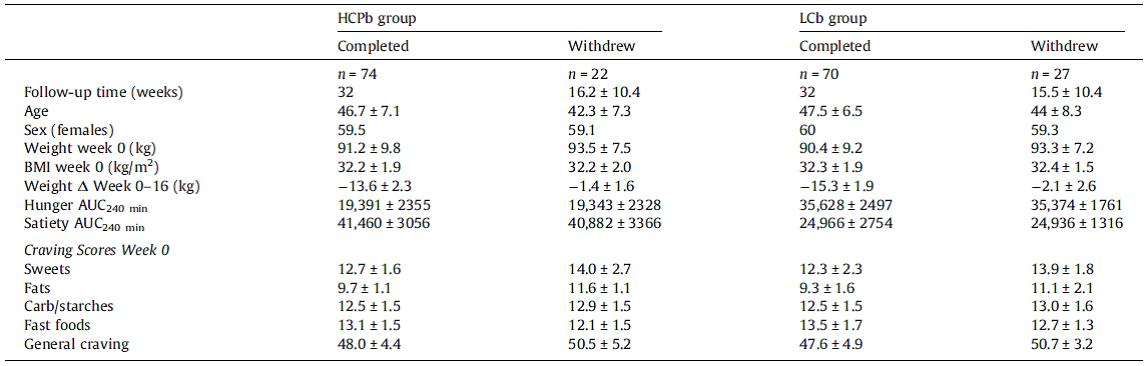

Table 2. There were no major differences between the groups, and between those who completed or didn’t complete the study except for weight loss in those who withdrew. Apparently, people who didn’t lose any weight on the hypocaloric weight loss diet decided to quit (was it the diet or the dieter that didn’t work? [sorry, no offense]). In any case, this would’ve introduced a systematic bias except the non-weight-losers were similar in both diet groups. But Hunger & Satiety was also similar between completers and dropouts… I wonder why… i.e., the diet was working for those who were losing weight, because Hunger was low and Satiety high; in the dropouts who didn’t lose weight, Hunger was low and Satiety high because they were eating more (which is why they didn’t lose weight). IOW: “not hungry -> eat less -> lose weight -> complete the study” vs. “eat more -> not hungry -> don’t lose weight -> dropout of the study.” People are “not hungry” in both groups, but for different reasons.

Critique 1b: this is another place where a food intake questionnaires would come in handy.

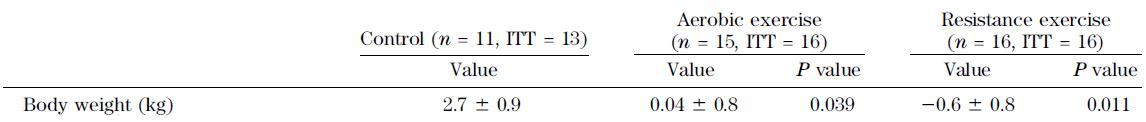

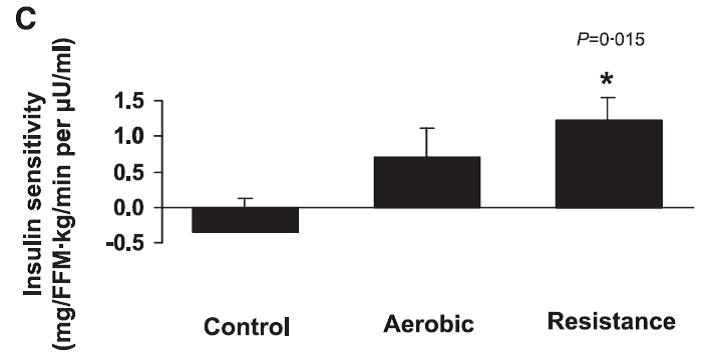

During the weight loss phase, LCb lost a little bit more weight and became a little bit more insulin sensitive than HCPb, which is interesting only because the macronutrients were so similar. Thus, it may have been an effect of “meal-size-timing.” In other words, don’t eat like a King for breakfast, a Prince for lunch, and a Pauper for dinner.

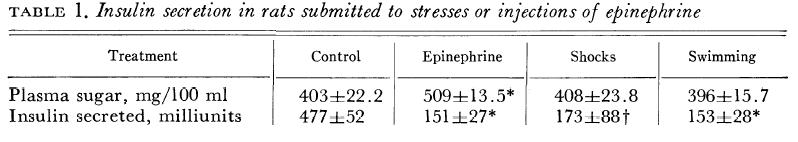

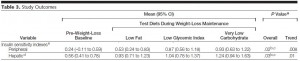

Ghrelin, a hunger hormone, was significantly higher in LCb and this actually correlated very well with measured Hunger levels (unlike leptin, the far more popular anti-hunger hormone, discussed in depth HERE). And insulin, a theorized yet controversial hunger hormone, did not: insulin was lower at week 16 while Hunger was 2x higher; and insulin was 2x higher at week 32 compared to week 16 while Hunger was the same at those time points (Table 3). Thus, for those interested (which is admittedly probably only me), neither leptin nor insulin correlate with Hunger levels; but this study showed that ghrelin does. Furthermore, similar to those leptin data mentioned above, Hunger was not correlated with weight loss (which is kind-of-fascinating).

The second half of the study (“weight-loss maintenance”) was complete bollocks and made no sense whatsoever (you’ll see it on the evening news). What you can conclude from this study, however: people following the moderately higher protein and lower carb pseudo-Dukan Diet (LCb) lost modestly more weight during the first 16 weeks than those following the more traditional higher carb version (HCPb). BOTH diets were “high protein” and “low carb,” and people in BOTH groups lost a lot of weight (~30 pounds in 4 months). The media hasn’t had their way this study [yet], but when they do, I’m sure the they’ll disagree.

(LCb) lost modestly more weight during the first 16 weeks than those following the more traditional higher carb version (HCPb). BOTH diets were “high protein” and “low carb,” and people in BOTH groups lost a lot of weight (~30 pounds in 4 months). The media hasn’t had their way this study [yet], but when they do, I’m sure the they’ll disagree.

Don’t eat doughnuts for breakfast, you heard it here first.

calories proper

(Stefansson, 1913)