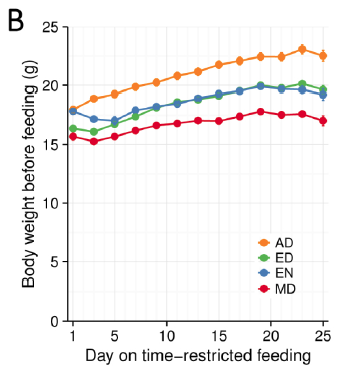

“Literally, every single model of skeletal muscle circadian arrhythmia mimics aging sedentary people who skip breakfast, stay up late, and get sick.”

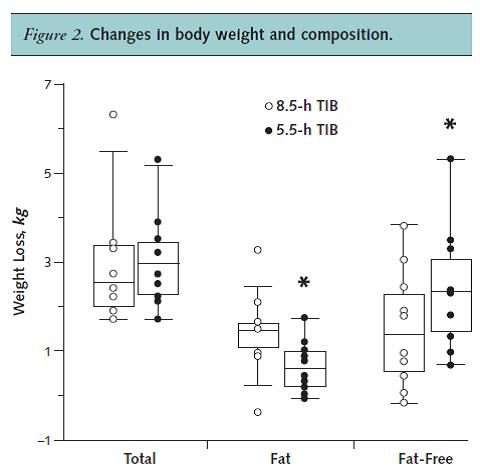

But first, the human studies that confirm these newer findings aren’t restricted to preclinical models: 1) a randomized CROSSOVER study; two weeks of modest caloric restriction. Same diet; either 5.5 or 8.5 hours of sleep.

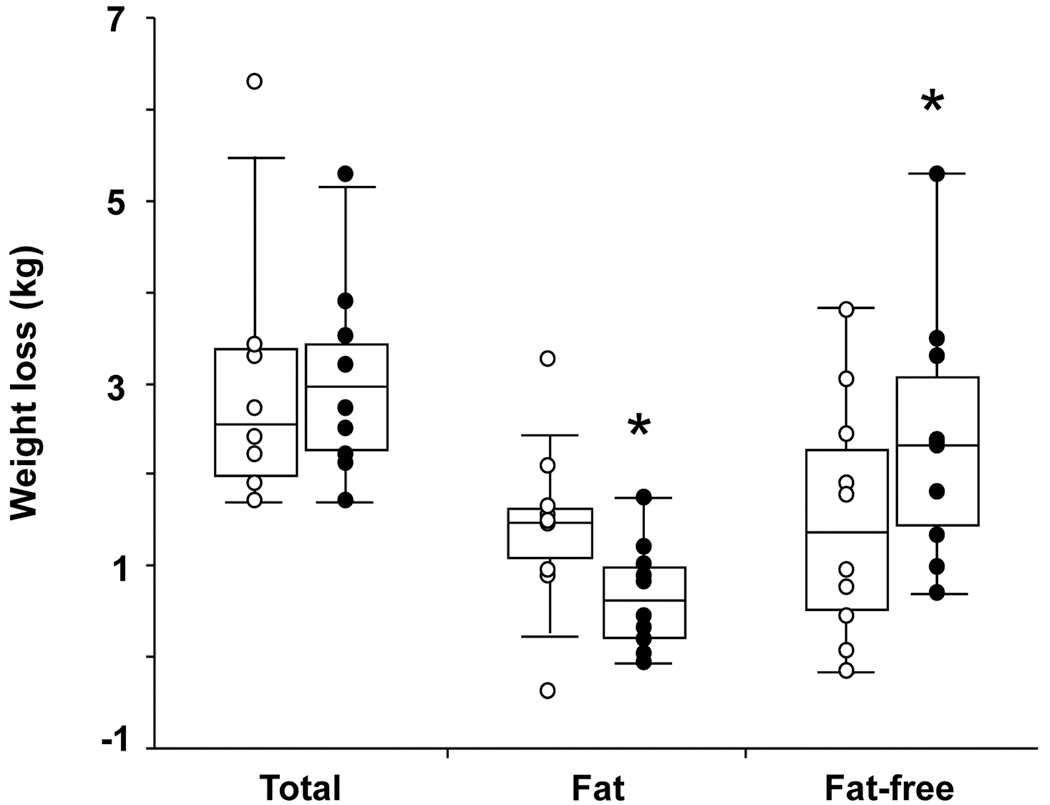

In other words, circadian rhythms broke or woke (Nedeltcheva et al., 2010):

Same diet & energy expenditure + circadian arrhythmia = lose less fat and more muscle. This is basically the opposite of optimal. Large error bars because it was a CROSSOVER study, although it still managed to reach statistical significance.

And this happened despite lower 24-hour insulin AUC (Nedeltcheva et al., 2012). GRAVITAS.

And in an ad lib setting, “Laboratory studies in healthy young volunteers have shown that experimental sleep restriction is associated with a dysregulation of the neuroendocrine control of appetite consistent with increased hunger and with alterations in parameters of glucose tolerance suggestive of an increased risk of diabetes” (Van Cauter et al., 2007).

Part 2. THE BETTER PART: The muscle clock, how it works, and how to fix it.

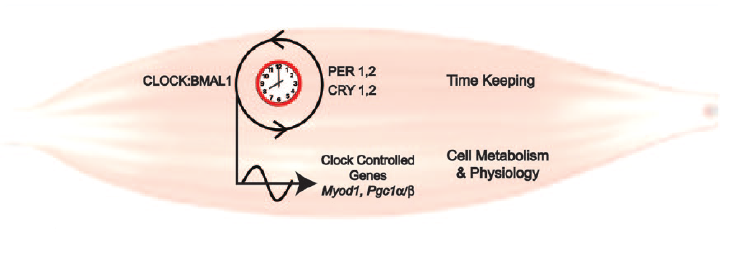

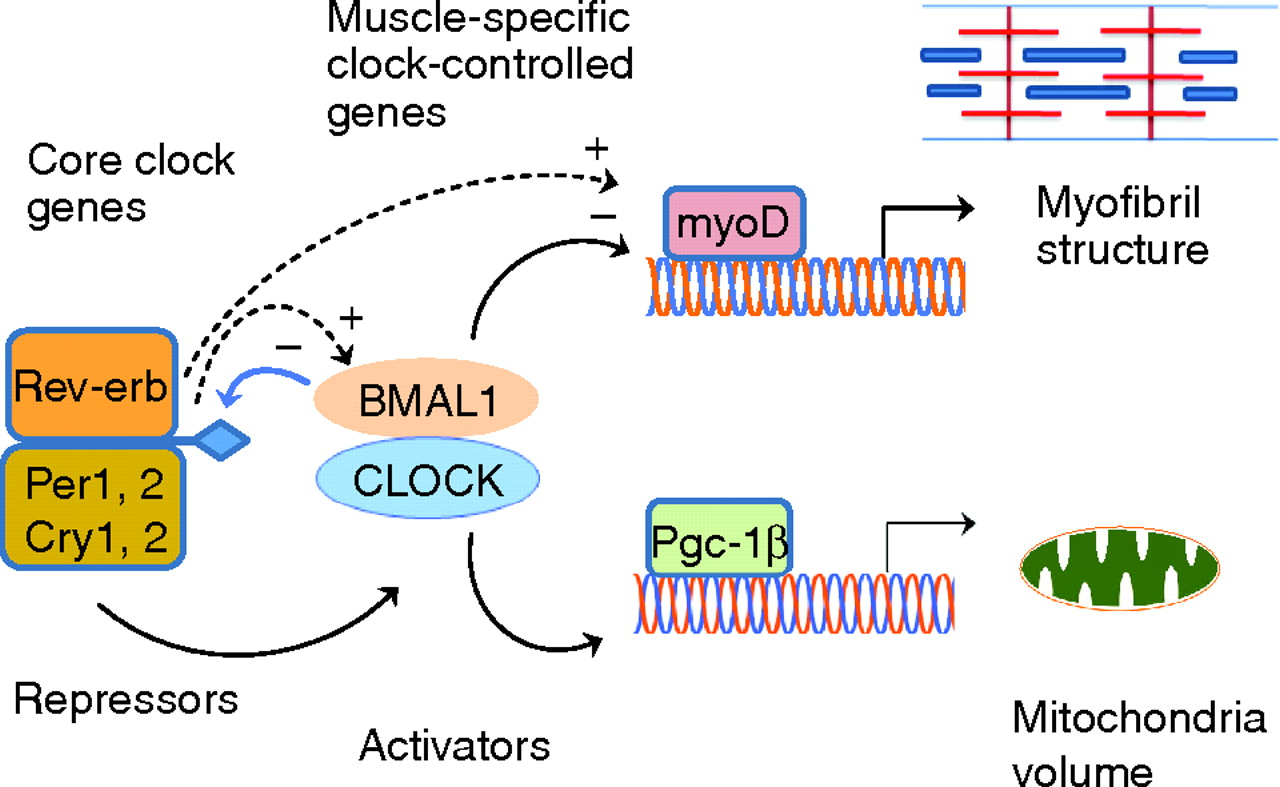

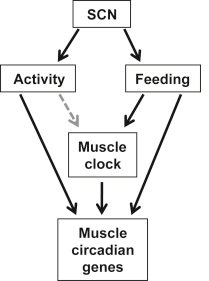

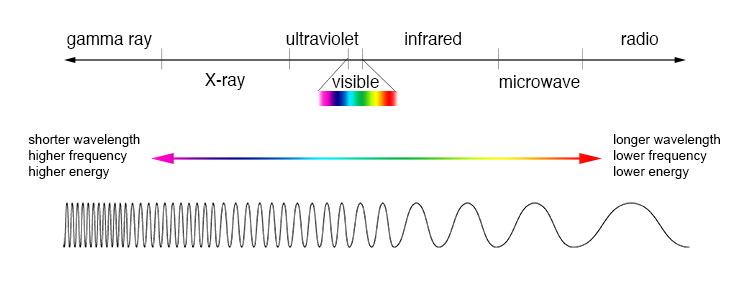

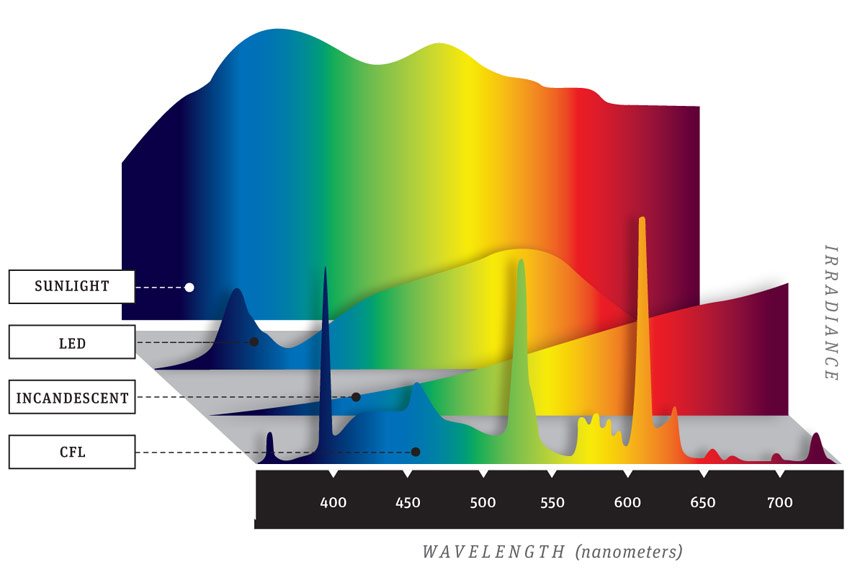

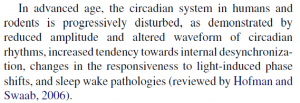

Similar to other peripheral circadian clocks (eg, liver, adipose, lung, etc.), the muscle clock is entrained by LIGHT via the central pacemaker located in the SCN and feeding (via an as of yet unclear mechanism), but also scheduled exercise.

Interestingly, mice who had been subjected to a 6-hour phase advance adapted faster if they exercised early in the active phase (would be morning for humans).

Much of these data are summarized in a review in Frontiers in Neuroscience (Aoyama and Shibata, 2017).

The muscle clock is entrained by timed exercise but also feeding. This was demonstrated by showing the circadian rhythms in a subset of muscle-specific genes in fed mice were absent in fasted mice.

It is thought that the muscle clock’s function is to prepare us for the transition from the resting/fasting phase (night) to the active/fed phase (day)… and although I like that phrasing, this seems somewhat subjective (and really hard to test/prove even on a hypothetical level).

Part 3. The BEST part: impact of various muscle clock disruptions.

Hint: THEY’RE ALL BAD.

For the rest of this article (including my interpretation and advice), head over to Patreon!

Three bucks a month for access to all articles and there are many other options. And it’s ad-free.

If you’re on the fence considering it, try it out, you can cancel at any time! Also, there is a limited number of positions remaining at the $3 level.

Lastly, I’m open to suggestions; please feel free leave a comment or email me directly at drlagakos@gmail.com.