The various studies on how low carbohydrate diets impact physical performance are very nuanced. Here’s what I mean by that.

Exhibit A. Phinney 1980

In this [pioneering] study, obese patients were subjected to a variety of performance assessments in a baseline period, then after 1 and 6 weeks of weight loss via protein-sparing modified fast (1.2 g/kg ideal body weight from lean meat, fish, or fowl; probably around 80 grams of protein/d, 500-750 kcal/d). They lost a lot of weight, 23 pounds on average, two-thirds of which was body fat. There was no exercise intervention, just the performance assessments.

(1.2 g/kg ideal body weight from lean meat, fish, or fowl; probably around 80 grams of protein/d, 500-750 kcal/d). They lost a lot of weight, 23 pounds on average, two-thirds of which was body fat. There was no exercise intervention, just the performance assessments.

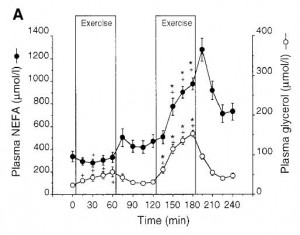

During the ‘exercise to exhaustion’ treadmill exercise, RQ steadily declined from baseline to week 1 to week 6, indicating progressively more reliance on fat oxidation. This was confirmed via muscle glycogen levels pre- and post-exercise: during the baseline testing, they declined by 15%; after 6 weeks of ketoadaptation, however, they only declined by 2%, while ‘time to exhaustion’ increased by 55%. After only 1 week of the diet, time to exhaustion plummeted, as expected, by 20%.

This was, as mentioned above, a pioneering study in the field of ketoadaptation. It also challenges one of the prevailing theories of ‘fatigue’ …while carb-adapted, the subjects fatigued after 168 minutes, with muscle glycogen levels of 1.29 (reduced by 15%); while ketoadapted, they fatigued after 249 minutes with muscle glycogen levels of 1.02 (reduced by 2%). In other words, they had less glycogen to begin with, used less glycogen during exercise, and performed significantly better (running on fat & ketones).

Exhibit B. Vogt 2003

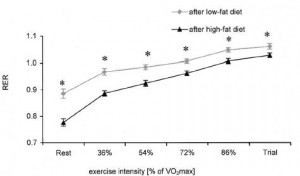

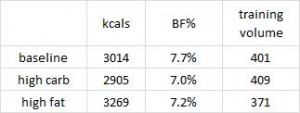

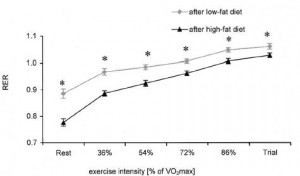

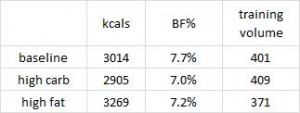

Highly trained endurance athletes followed a high fat (53% fat, 32% carbs) or high carb (17% fat, 68% carbs) diet for 5 weeks in a randomized crossover study. In contrast to Phinney’s study, these participants were: 1) highly trained; and 2) exercised throughout the study.

Maximal power output and VO2max during a similar ‘time to exhaustion’ test was similar after both diet periods. Same for total work output during a 20 minute ‘all-out’ cycling time trial and half-marathon running time. Muscle glycogen was modestly, albeit statistically non-significantly lower after ketoadaption; however, ketoadapted athletes relied on a higher proportion of fat oxidation to fuel performance as indicated by lower RQ at every level of exercise intensity:

as indicated by lower RQ at every level of exercise intensity:

Again, this is the essence of ketoadaptation. Physical performance as good as or better using fat and fat-derived fuels.

One reason Phinney’s glycogen-depeleted ketoadapted subjects may have done so well is their reliance on ketones (probable) and intramyocellular lipids (IMCL) (possible). In Vogt’s study, IMCL increased from 0.69 to 1.54% after ketoadaptation…

Also, food intake and body fat declined, and training volume increased in the low fat group; whereas food intake increased, and body fat and training volume declined in the high fat group. Reminiscent of anything?

High fat, low carb -> eat more, exercise less, STILL LOSE BODY FAT.

Sorcery? No. Diet impacts more than just mood and body composition – resting energy expenditure increased in the ketogenic dieters. This isn’t an isolated finding.

Exhibit C. Fleming 2003

This was another study in non-trained athletes, consuming high fat (61% fat) or control (25% fat) diets for 6 weeks. The tests were the 30-second Wingate, to examine supramaximal performance, and a 45-minute timed ride, to examine submaximal performance.

This study differed from the previous two in several significant ways. For starters, peak power output declined in both groups, slightly more so in the high fat group (-10% vs. -8%). Furthermore, RQ didn’t wasn’t significantly lower during this test in the high fat group, which possibly suggests they weren’t properly ketoadapted. In Phinney’s study, the large energy deficit ensured ketoadaptation; this study lacked that aspect, somewhat more similar to Vogt’s, although unlike Vogt’s, these participants weren’t athletes which presumably makes ketoadaptation more difficult.

There are many factors at play… I wasn’t kidding when I said these studies are very nuanced!

Exhibit D. the infamous, Paoli 2012

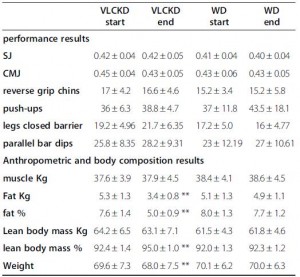

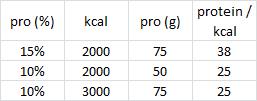

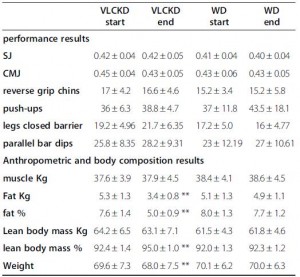

These were ‘elite artistic gymnasts,’ who could likely beat you in a race running backwards. The ketogenic phase consisted of 55% fat and much more protein than the control phase (39% fat; protein: 41% vs. 15%). The significantly higher protein content was modestly offset by slightly more calories in the control phase, which reduces the amount of protein required to maintain nitrogen balance.

In this study, performance was, for the most part, ‘maintained,’ with relative increases in a few of the tests; eg, the “legs closed barrier.” Changes in body composition were more robust: significantly reduced body fat and increased lean body mass after 30 days of ketogenic dieting (with their normal exercise routine).

The major confounder in this study was the use of an herbal cocktail only in the ketogenic diet group; despite this, the results are largely in line with the other studies. For more on this study, see here.

Exhibit E. the most dramatic one to date: Sawyer 2013

Please see here for the details, but in brief, strength-trained athletes showed improvements in high intensity exercise performance after only 7 days of carbohydrate restriction. The nuances of this particular study are discussed more here.

Collectively, these studies show that physical performance in both endurance and high intensity realms does not always suffer, can be maintained, and in some cases is improved by ketogenic dieting. Important factors are duration (to ensure adequate ketoadaptation), energy balance, and regular physical activity (athletes and regular exercisers can adapt to burning fat much quicker than sedentary folks).

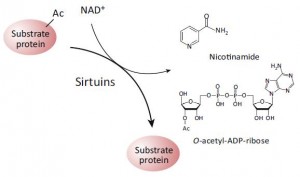

calories proper

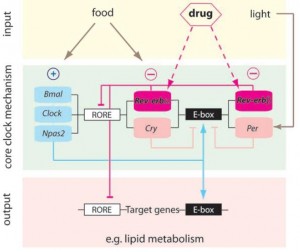

(which may or may not be acting through SIRT1; this is controversial). While alcohol does no great favors for circadian biology, if you’re going to imbibe, perhaps a resveratrol-rich Argentinian malbec served, and this might be the important part, at night, when all of this stuff is going on… coincidentally [fortunately], that’s precisely when most choose to imbibe.