It has to do with the duration of time spent being sedentary.

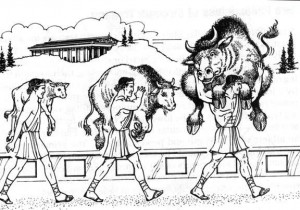

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but luckily enough today you get both.

Sarcopenia: “poverty of flesh,” or the age-induced loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function = reduced quality of life. Sorry old-timers, but I hereby officially revise the definition from “aging-induced” to “sedentary-induced.” Herein, I present evidence that sarcopenia is not a phenomenon of aging per se, but rather of disuse atrophy. Dear Webster’s & Britannica, please revise accordingly.

Skeletal muscles: use ‘em or lose ‘em #TPMC

Thanks to Julianne Taylor & Skyler Tanner for directing me to these images.

divide and conquer

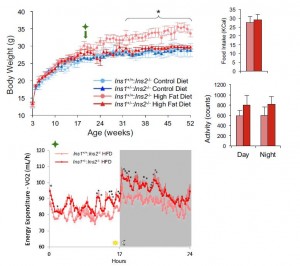

Exhibit A. Chronic exercise preserves lean muscle mass in masters athletes (Wroblewski et al., 2011)

This study evaluated “high-level recreational athletes.” “Masters” just means they were over 40. And “high-level” doesn’t mean “elite,” it just means they exercised 4-5 times per week. These weren’t super-obsessed gym rats… it’s probably who I’ll be in 7 years [sigh].