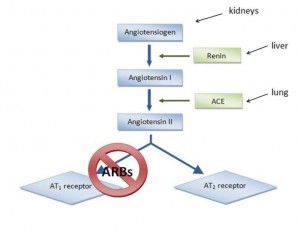

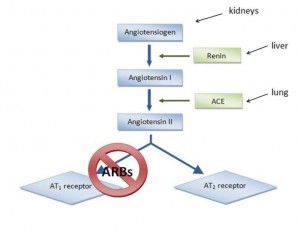

Pathologically low blood pressure can lead to shock & death. Angiotensin II is there to prevent that, but it does much more. A bit non-sequiter, perhaps.

This is what I call teamwork: low blood pressure detected by kidneys –> secretes renin. Angiotensinogen (liver) is cleaved by renin to Angiotensin I. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (lungs [among other tissues]) cleaves angiotensin I into angiotensin II.

Angiotensin II increases blood volume and restores blood pressure. Good if you’ve lost a ton of blood fighting a wild beast; not good if you’re an overweight pen pusher on potato chips. ACE inhibitors reduce angiotensin II, lowering blood pressure. ACE is present in lungs probably because it deactivates bradykinin. ACE inhibitors prevent this which might contribute to one of their side effects, a persistent dry cough which makes these drugs intolerable for many. One alternative is angiotensin II receptor 1 blockers, or “ARBs.”

If anyone in pharma reads my blog (doubtful, unless they are monitoring for people to polonium-laced blow-dart), this will be their favorite post because I think ARBs are an interesting class of drugs.

If diet and weight loss are inadequate, telmisartan might be the next best thing to manage hypertension in diabetics: Telmisartan for the reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Verdecchia et al., 2011) –> effective at reducing mortality in patients with diabetes.

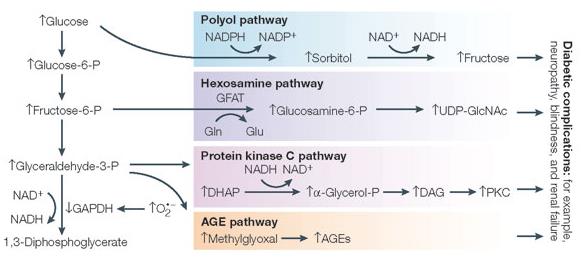

Efficacy of RAS blockers on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in NIDDM (Cae & Cooper 2012) –> reduces morbidity and slows progression of renal disease (both hypertension and diabetes contribute to [irreversible] kidney damage, and frequently occur together, which makes this endpoint particularly relevant). Hyperglycemia should be managed via diet, of course, and ARBs would need to be tested in people following something other than a Western diet (although said people may not even need treatment in the first place) (just thinking out loud here. Or typing/whatever.)

But enough about blood pressure (<– boring); on to the more interesting stuff:

It started here: Chronic perfusion of angiotensin II causes cognitive dysfunctions and anxiety in mice (Duchemin et al., 2013)

Then: Candesartan prevents impairment of recall caused by repeated stress in rats (Braszko et al., 2012)

And: Anti-stress and anxiolytic effects of [candesartan] (Saavedra et al., 2005)

[Candesartan] prevents the isolation stress-induced decrease in cortical CRF1 receptor and benzodiazepine binding (Saavedra et al., 2006)

[Candesartan] ameliorates brain inflammation (Benicky et al., 2011) brain inflammation induced by chronic exposure to artificial lights causes depression-like symptoms (in mice) (probably humans, too)

Finally, a human study: Candesartan and cognitive decline in older patients with hypertension (Saxby et al., 2008)

And then there’s this: Angiotensin receptor blockers for bipolar disorder (de Gois et al., 2013)

No mechanistic stuff because, well, I have no idea how it works. On one hand, it might seem obvious that stress & anxiety can raise blood pressure, so something that lowers stress & anxiety could lower blood pressure. Candesartan appears to do both (cause <–> effect?). There are two unique properties of candesartan to note: 1) it gets into the brain; and 2) it leads to increased levels of angiotensin II (which presumably can’t do much because candesartan blocks the receptor for angiotensin II). Perhaps angiotensin II targets a different receptor? ARBs might blunt angiotensin II-induced CRH secretion, leading to anxiolysis, stress-tolerance, and pro-cognitive effects (that speculation was made possible by a thread on Avant Labs’ Forum and a few posts by Jane Plain on CRH [eg, here & here]).

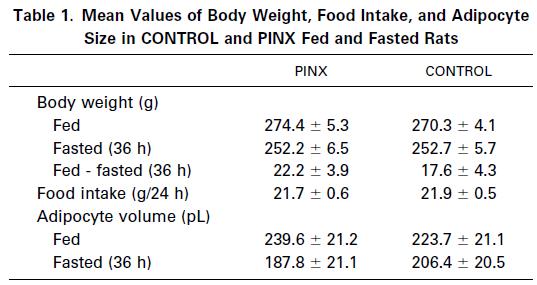

Oh yeah, ARBs also prevent cafeteria diet-induced weight gain, insulin resistance, and ovulatory dysfunction [in rats] (Sagae et al., 2013). And are sympatholytic like bromocriptine (Kishi & Hirooka 2013).

“The Angiotensin-melatonin axis” (Campos et al., 2013).

just sayin’

calories proper