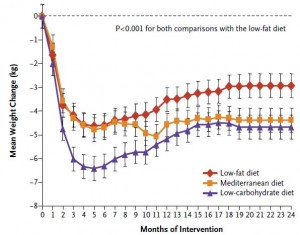

While statisticians try to wheedle causation from observational data, they really just end up showing us what health conscious people are like. They exercise more and smoke less, eat more fruit and less red meat, etc. This doesn’t “prove” those habits actually make health conscious people healthy. Intervention studies, where healthy and non-healthy people are randomly assigned one of those habits, are required in order to achieve any reasonable amount of “proof.” With regard to red meat, findings from such studies frequently stand in contrast to the observational data.

-end soapbox-

Divide and conquer

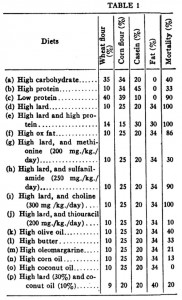

Serum lipids in humans fed diets containing beef or fish and poultry (Flynn et al., 1981 AJCN)

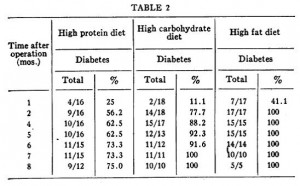

randomized crossover study: 1 egg + 5 oz. of red meat or fish/poultry for three months

The red meat group ate significantly more cholesterol than the poultry/fish group (540 vs. 477 mg/d), fat (104 vs. 83 g/d) and saturated fat (40 vs. 27 g/d). Despite these differences, there were no changes in serum cholesterol or HDL. In women but not men, red meat decreased and poultry/fish increased serum triacylglycerols, an effect that was consistent regardless of the order in which the diets were consumed (it was a crossover study). This is significant because according to the Framingham studies, serum triacylglycerols are a more important predictor of heart disease in women than men. And interestingly, carb intake, which usually regulates serum triacylglycerols, was similar in both groups suggesting that red meat has a triacylglycerol-lowering effect independent from simply displacing carbs from the diet. Furthermore, the red meat group consistently ate about 200 more kilocalories then the poultry/fish group yet body weight was stable and similar in both groups.

Conclusion 1: 5 ounces of red meat (plus more cholesterol, fat, and saturated fat) for three months lowered serum triacylglycerols and didn’t affect cholesterol. The excess calories consumed in the red meat group (mostly from saturated fat and protein) didn’t cause weight gain.

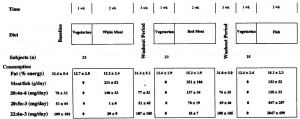

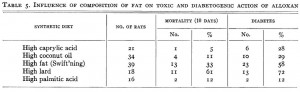

The effect of short-term diets rich in fish, red meat, or white meat on thromboxane and prostacyclin synthesis in humans (Mann et al., 1997 Lipids)

randomized intervention study: ~8 oz. white meat vs. ~12 oz. red meat vs. ~5 oz. fish for 2 weeks

This study was really trying to compare the effect on inflammatory markers of the high AA content of meat to the high EPA and DHA in fish (AA being pro-inflammatory and EPA/DHA being anti-inflammatory). As expected, the fish diet reduced inflammatory biomarkers (thromboxane and prostacyclin). The two unexpected findings were: 1) white meat actually increased inflammatory biomarkers, and 2) red meat had no effect.

As expected, the fish diet reduced inflammatory biomarkers (thromboxane and prostacyclin). The two unexpected findings were: 1) white meat actually increased inflammatory biomarkers, and 2) red meat had no effect.

Conclusion 2: red meat and AA did not impact the inflammatory biomarkers thromboxane and prostacyclin.

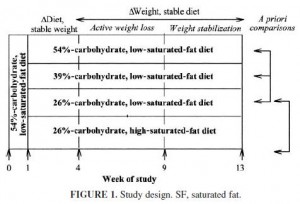

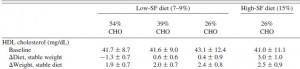

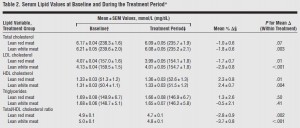

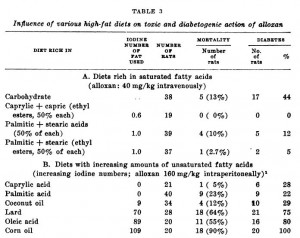

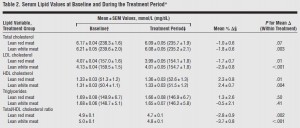

Comparison of the effects of lean red meat vs lean white meat on serum lipid levels among free-living persons with hypercholesterolemia (Davidson et al., 1999 Archives of Internal Medicine)

randomized intervention study: ~5 oz/d of red meats (beef, veal, and pork) vs. white meats (poultry and fish) for 36 weeks

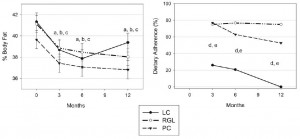

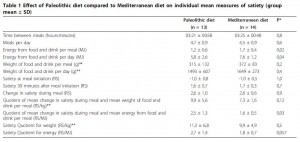

As seen in the table below, neither diet had any major effect on plasma lipids.

Fat, cholesterol, and total calorie intake was higher in the red meat group, but again, this didn’t result in any differences in body weight between the groups.

Conclusion 3: red meat had no effect on plasma lipids and the excess calories consumed in the red meat group (mostly from saturated fat and protein) didn’t cause weight gain.

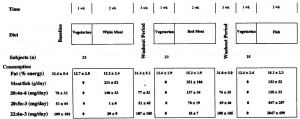

Partial substitution of carbohydrate intake with protein intake from lean red meat lowers blood pressure in hypertensive persons (Hodgson et al., 2006 AJCN)

randomized intervention study: 2 oz./d red meat vs. starchy carbs for 8 weeks

Conclusion 4: red meat lowered blood pressure and the excess calories consumed in the red meat group (mostly from saturated fat and protein) didn’t cause weight gain.

Increased lean red meat intake does not elevate markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in humans (Hodgson et al., 2007 AJCN)

randomized intervention study: 8 oz./d of red meat vs. carbs for 8 weeks

Subjects were instructed to eat their red meat in place of carb-rich foods such as bread, pasta, rice, potatoes, and breakfast cereals.

Conclusion 5: Biomarkers of oxidative stress (F2 isoprostanes and GGT) and inflammation (CRP and SAA) were reduced in the red meat group.

In sum:

WRT plasma lipids: red meat improved some and had no effect on others

WRT inflammation: red meat had no effect on thromboxane and prostacyclin, and decreased CRP and SAA

WRT oxidative stress: red meat reduced F2 isoprostanes and GGT

WRT energy balance: the excess calories from red meat didn’t cause weight gain. This was the most consistent finding in all of the above studies and may be at least partially explained by the findings of the recent protein overfeeding study by George Bray and colleagues who showed, in brief, that excess protein had no impact on fat mass and actually increased lean mass. So if you’re worried that fatty red meat might make you fat, don’t be.

The key to these 5 studies is that they are randomized intervention trials. It’s not simply looking at what healthy people eat, but rather what happens when one specific dietary component is changed in all kinds of random people. In other words, it’s what would happen in the real world if you made this dietary change. And red meat consistently improved a variety of health parameters.

I suspect when the value of intervention trials is realized and fully appreciated, the habits of health conscious people will change. Until then, we’ll just have to take the media’s reporting of nutrition studies with a grain of salt.

If you like what I do and want to support it, check out Patreon! $5/month for full access to all articles and you can cancel if it sucks 🙂

For personalized health consulting services: drlagakos@gmail.com.

Affiliate links that probably don’t work anymore: Still looking for a pair of hot blue blockers? TrueDark is offering 10% off HERE and Spectra479 is offering 15% off HERE. Use discount code LAGAKOS for a deal on CarbonShades. If you have no idea what I’m talking about, read this then this.

OMAHA. STEAKS. Check here for daily discounts and the best steaks of your life.

Keto-mojo.

Naked Nutrition makes some great products, including Naked Grass Fed Protein. Also, free shipping

20% off some delish stocks and broths from Kettle and Fire HERE.

Real Mushrooms makes great extracts. 10% off with coupon code LAGAKOS. I recommend Lion’s Mane for the brain and Reishi for everything else.

calories proper