Next time someone says VLC/keto is harmful or at least not helpful for fat loss because of a new rodent study, they’ll probably be wrong.

BOOKMARK THIS ONE GUYS.

Rodent studies on ketogenic diets or exogenous ketones are valuable and interesting in a variety of #contexts, although I’d argue that regulation of fat mass isn’t really one of ’em.

For starters, rodents aren’t particularly ketogenic – it’s rare to see ketones >1 after an overnight fast even in long-term ketoadapted mice. Also, many rodents gain weight until they die, whereas humans plateau and stay relatively weight-stable for their entire lives (at least historically, and I’m not talking about yo-yo dieting).

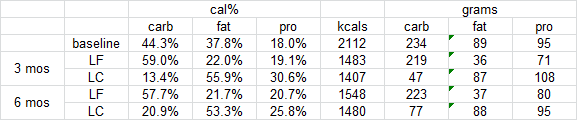

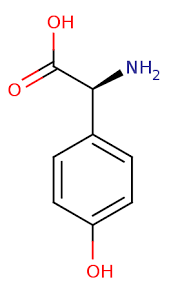

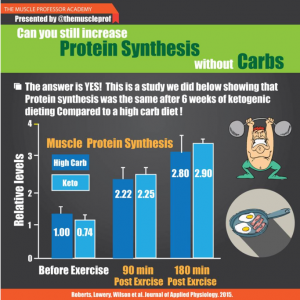

Skeletal muscle, on the other hand, seems more similarly regulated: keto isn’t muscle-sparing in either specie… most people, perhaps unwittingly, increase protein intake on keto, and THIS spares muscle (N.B. this is simply to spare muscle, whereas in non-keto dieters, it’s not uncommon to see increased muscle in the #context of high protein). That’s because carbs are more anabolic than fat. QED.

There’s just a fundamental difference in the way fat mass and appetite is regulated between the species. There are many similarities, which is why these studies are still valuable, but fat mass isn’t one of ‘em.