A fundamental reevaluation of the concept of “dieting”

But first, an ode to energy balance:

Diet and exercise, or diet alone,

But “exercise only” does naught but tone.

Exercise is effective for weight loss if and only if it’s accompanied by dieting, not vice versa. Enter: the best experiment ever.

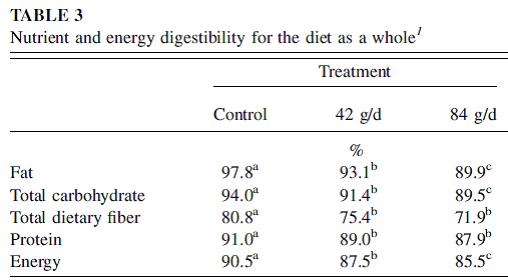

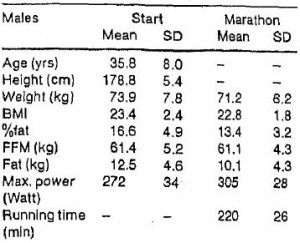

Exhibit A. Food intake and body composition in novice athletes during a training period to run a marathon (Janssen, Graef, and Saris, 1989)

This is, in its most purest form, an isolated “exercise only” intervention. Volunteers were recruited to train for a marathon; no dietary advice given. That is a critical point. In order to test exclusively “exercise only,” you can’t have a group of people who are trying to lose weight via exercise because if weight loss is their goal, watching what they ate would happen automatically and we would not truly have “exercise only.” This isn’t a diet study; indeed, that’s the point. Lastly, regardless of the data, it’s hard to say this was an inadequate exercise intervention. Training for a marathon is no easy task; after 18 months (of “exercise only”), they completed a full marathon in just under 4 hours. IMHO this confirms they were exercising quite intensely for the entire 18 months. They started this adventure weighing 162 lbs and ended at 157. If they gained 10 pounds of muscle and lost 15 pounds of fat, then they’d be 5 pounds lighter and I’d be training for a marathon. But that’s not what happened. They lost 5 pounds, and only about half of it was fat.

They started this adventure weighing 162 lbs and ended at 157. If they gained 10 pounds of muscle and lost 15 pounds of fat, then they’d be 5 pounds lighter and I’d be training for a marathon. But that’s not what happened. They lost 5 pounds, and only about half of it was fat.

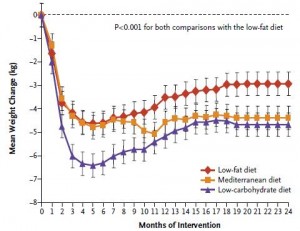

Side note: train for a marathon vs. a calorie non-restricted diet for weight loss? In the [notorious] Shai study, people assigned to the low carb diet were allowed to eat as much as they wanted as long as it was low carb. To put things into perspective, after 18 months low carb dieters lost over twice as much weight as the marathon runners, and they weren’t exercising.

Moving on,

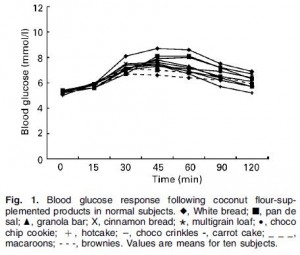

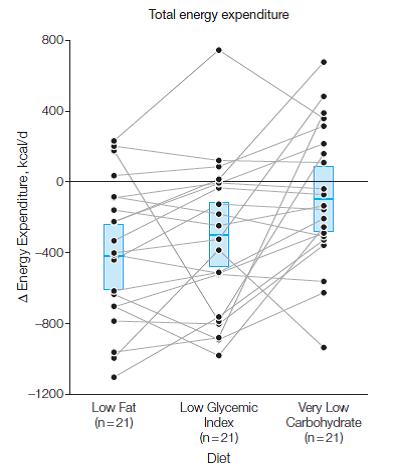

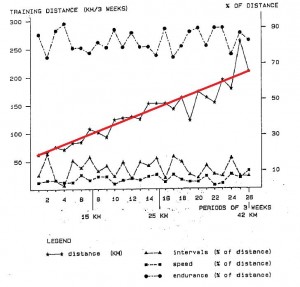

5 pounds of weight loss is much less than expected after 18 months of marathon training. By the end of the study they were running an average of 9 kilometers per day (see the red line in the figure below).

So why didn’t they lose more weight? In brief, exercise made them hungry, and by the end of the study they were eating an additional 400 kilocalories daily. I imagine running 9 km burns slightly more than 400 kcal, which is why they lost a few pounds in the process. Had they been dieting, they would’ve lost a lot more and this study would no longer be a test of “exercise only.”

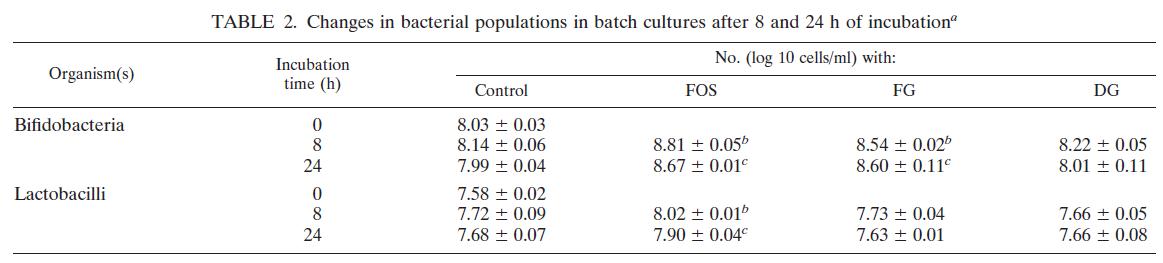

Exhibit B. Effect of exercise alone on the weight of obese women (Gwinup, 1975)

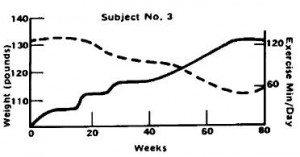

In this weight-loss study, Gwinup claims it is “exercise alone” because it was a group of women who failed to lose weight via dieting and [sic] “were, therefore, most amenable to an attempt to control weight with exercise alone.” These women had been trying to lose weight for a while, so it’s very likely they were always watching what they ate (unlike the people recruited for the marathon study). Gwinup’s exercise intervention was simple: walking. And for some lucky women, it worked. Take subject number 3, for example: a 37 year old housewife who had been trying to lose weight since she was 20. By gradually increasing her walking time to just over 2 hours per day, she was able to lose ~ 15 pounds after 18 months. P.S. that’s not 2 hours including regular daily activities; it’s 2 hours of dedicated exercise time.

But I don’t think this was truly “exercise only.” It takes about an hour to jog 9 km. The marathon runners were almost in energy balance ingesting 400 additional kcal suggesting a 9 km jog burns a tad over 400 kcal.

Subject number 3 was walking for two hours (6 km?), yet she lost 15 pounds over the same time period (18 months): 1. her energy deficit was greater than the marathon runners; 2. she lost more weight despite exercising less; 3. the marathon runners were NOT dieting, so “not dieting” results in 5 pounds of weight loss; 4. subject number 3 was exercising less than the marathon runners; if she too was “not dieting,” she could not have lost more weight than the marathon runners; 5. ergo, subject number 3 was not “lucky,” she was dieting.

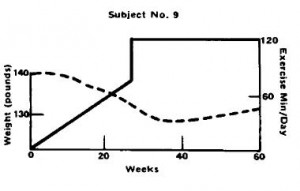

Subject number 9, on the other hand, a younger housewife who had only been trying to lose weight for 3 years despite being 7 pounds heavier than subject number 3, was not so “lucky.”

Subject number 9’s exercise duration was similar (2 hours per day), and for the first half of the study, things were going great, she dropped 10 pounds. But for the second half of the study, she was gaining it back. Recruitment inclusion criteria included women who regained weight they lost via diet alone. So either subject number 9 is biologically resistant to both diet- and exercise-induced weight loss, or she just likes to eat. To be clear, regarding the second half of subject number 9’s progress: 1. “exercise only;” 2. TWO hours per day; 3. body weight is steadily increasing.

Exercise worked for subject number 3 because she was dieting; it didn’t for subject number 9 and the marathon runners because they weren’t.

calories proper