or the next big thing in functional foods, Op. 84

Altered gut bacteria can cause a whole host of problems, anywhere from depression and fatigue to ADHD and heartburn. Thus, while running my daily search for “bifidobacteria,” I happened across these little goodies:

The Attune Foods Dark Chocolate Probiotic Bar. Combining probiotics (e.g., bifidobacteria, acidophilus, etc.) with chocolate?! And with 68% cocoa, I’d expect this bar to deliver at least some of the benefits of dark chocolate (e.g., improved insulin sensitivity). They’re gluten-free and even contain inulin

! (my second favorite bifidogenic prebiotic.)

And it packs a big, or rather huge, probiotic punch (6.1 billion B. lactis HN019, L. acidophilus NCFM, & L. casei LC-11). Attune loses a little cred by trying to disguise their sugar as “evaporated cane juice,” like it’s something inherently healthier than plain old sugar… just like all-natural agave syrup, honey, and organic coconut blossom sugar. just own it for crying out loud. On the other hand, at only 6 grams, the sugar in Attune’s bar is harmless especially in the context of the high cocoa content, inclusion of inulin, and whopping dose of probiotics.

But, chocolate & probiotics? Alas, the curiousity bug had bitten.

Apparently, a lot of companies think dark chocolate is a good vehicle for probiotic delivery.

GI Health’s Probiotic Chocolate

GI Health’s Probiotic Chocolate is gluten-free and contains a half billion L. helveticus R0052 and B. longum R0175 per serving. A half-billion is low by conventional standards*, but such standards might be irrelevant if the delivery vehicle (i.e., chocolate) is superior.

*Most probiotic products are rated (by me) by the number of live bacteria per serving, or “colony forming units (cfu).” This is usually in the billions because most die in transit, thus the importance of the delivery method. Yogurt and apparently now chocolate seem to be good delivery vehicles, however, yogurt and most probiotic pills require refrigeration; these chocolate products do not. And neither do Nature’s Way Probifia Pearls, although they are the only pill that doesn’t (I suspect alien technology).

gimme Probiotics Dark Chocolate Candies, Youngevity Triple Treat

; the list goes on and on. Apparently, I was late to the game… (expect to see these in your local grocer soon.)

Enough shameless promotion, what about the data?

Possemiers (2010) set out to test how well probiotics survived in a robot gut simulator when mixed in chocolate. 1 billion L. helveticus CNCM I-1722 and B. longum CNCM I-3470 were mixed with either chocolate or milk. An astounding 85% of the probiotics survived when administered in chocolate compared to only 25% with milk. FYI the study was funded by Barry Callebaut, a fancy Belgian chocolate maker who is currently developing their own line of probiotic chocolates … it’s not a conflict of interest, it’s what companies should be doing IMO (while an independent third party would be optimal, any data are better than none). I have no idea how well their robot gut simulator emulates actual human digestion, but these results suggest that chocolate is [at least] potentially a good candidate to deliver probiotics.

An additional benefit of loading probiotics into chocolate is that cocoa itself can function as a prebiotic. Tzounis (2011) gave real-life live humans cocoa every day for 4 weeks and showed that bifidobacteria increased dramatically. These findings were confirmed by Fogliano (2011), who showed (via another robotic gut simulator) that water-insoluble cocoa fractions (e.g., cocoa fiber) alone markedly stimulated the growth of bifidobacteria.

So: 1) chocolate is a good vehicle to deliver exogenous bifidobacteria; and 2) cocoa promotes the growth of endogenous bifidobacteria. win-win.

Why is this relevant? because probiotics by themselves don’t survive the trip! They die off somewhere between the factory and your large intestine. In a study by Prilassnig (2007), 7 people were fed one of 6 different commercially available probiotics for a week. 2 of the products contained bifidobacteria, Omniflora and Infloran. None of the bifido in Omniflora survived in any of the volunteers, and the bifido in Infloran was detectable in only 1 out of 4. Feeling lucky?

Thus, chocolate may be not only viable, but an optimal way to administer probiotics. The bifidobacteria can feed on the cocoa while in transit (from the factory to your cupboard to your bowels), and the cocoa can directly stimulate them along with your native gut flora.

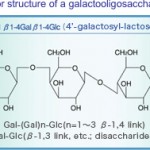

And chocolate with GOS?! according to Davis (2010), chocolates enriched with 10 grams of GOS increased endogenous bifidobacteria a whopping 3-fold.

Formula for the healthiest chocolate on Earth? >70% cocoa, a billion bifidobacteria, and a few grams of GOS… don’t get your hopes up, however, this won’t likely be made any time soon. Despite all of the data showing the remarkable health-promoting properties of GOS, it’s still not widely commercially available. In the meantime, Attune’s use of inulin will have to suffice.