or

Weight-loss maintenance, part II (as promised)

Effects of dietary composition on energy expenditure during weight-loss maintenance (Ebbeling et al., 2012)

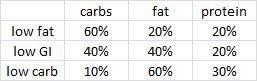

A three-way crossover study! Excellent study design. In brief, the participants lost 30 pounds in 12 weeks on a pseudo-Zone diet (the official version

) consisting of 45% carbs, 30% fat, and 25% protein, then switched to one of 3 “weight-loss maintenance” diets for 4 weeks. (FTR “weight-loss maintenance” cannot even be remotely assessed in 4 weeks, but what the heck, it was a THREE-WAY CROSSOVER.)

To put the issue to bed before it is even raised, the volunteers were given professionally prepared food for about half a year and paid ~$2,500 if they stuck to the plan. They STUCK to the plan.

The diets were classified by the authors as high glycemic load (high carb low fat), low glycemic index (e.g., Mediterranean Diet), & low carb (e.g., Atkins Diet

).

These “glycemic” indices in general are primarily determined by the carb & fat contents. A low carb diet will always have a low glycemic index and low glycemic load, and the opposite is true for a low fat high carb diet. Any high glycemic index food turns into a low glycemic index meal when it’s combined with other foods (like we normally eat). The only way to make a strictly high GI diet is with low fat; the easiest way to make a low GI diet is with low carb.

The major outcome measurements dealt with energy expenditure, with the premise being that preservation of metabolic rate after weight loss should improve “weight-loss maintenance.”

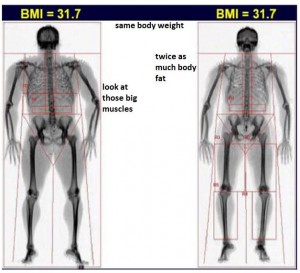

Resting energy expenditure (REE) is measured by indirect calorimetry. It’s the amount of calories that a total couch potato would burn daily and is usually determined by body composition (more muscle = higher REE). While body composition was similar in each group, REE was modestly higher in subjects on the low carb diet.

RQ (respiratory quotient) measures the relative amount of fat and carbs you’re burning: 0.7 = fat oxidation; 1.0 = carb oxidation. It is determined by diet (eat more carbs, burn more carbs), body composition (have more body fat, burn more body fat), and exercise intensity (marathons burn fat; sprints burn carbs). The higher carb oxidation on the low fat diet and higher fat oxidation on the low carb diet likely reflect the respective dietary compositions.

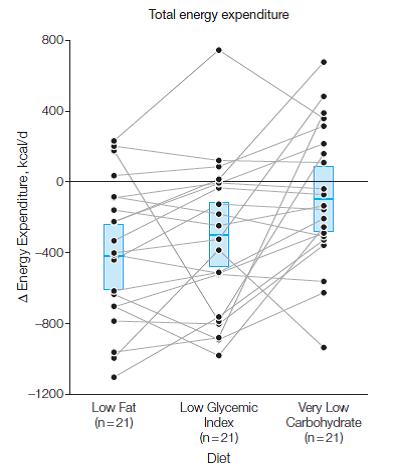

Total energy expenditure (TEE) is exactly what its name implies. It’s the total amount of calories you burn in a day. If your body weight is stable, then this is also approximately how many calories you’re eating. This result is actually pretty interesting. TEE on the low carb diet was over 300 kcal higher relative to the low fat diet. This is probably at least partially due to the higher protein content of the diet (30% vs. 20% of total calories or 150 vs. 100 grams per day). TEE of the intermediate low GI diet was in between low fat and low carb diets (2937 kcal/d), so TEE increased as carb intake declined and fat intake increased across all 3 diet groups. Follow the blue boxes in the figure below to see the averages, and since this was a THREE-WAY CROSSOVER (!), you can follow the lines to see how each person fared individually:

300 kcal is equivalent to an hour of exercise, yet subjects on low carb weren’t exercising more (although the slowly-losing-his-wits-Dr Bray suggested otherwise in an editorial, arguing that the increased TEE/REE ratio meant increased physical activity, despite the actual data, which showed if anything, slightly lower total and moderate-vigorous intensity physical activity in the low carb group).

Burning an additional 300 kcal per day is like losing over 2 pounds of fat per month by doing exactly nothing. BUT

to be clear (e.g., disclaimer, mea culpa, evidence of heresy, etc.):

- all participants in the study ate the same amount of calories

- low carbers burned over 300 more calories per day compared to low fat dieters

- body composition and body weight were similar between the groups

300 calories per day is a LOT of calories, why didn’t it impact weight loss?

This seemingly paradoxical conclusion suggests energy intake is the primary determinant of weight loss, independent of energy expenditure and diet composition. It is either a violation of The Laws of Energy Balance, experimental error, or evidence of dark magic.

Moving on,

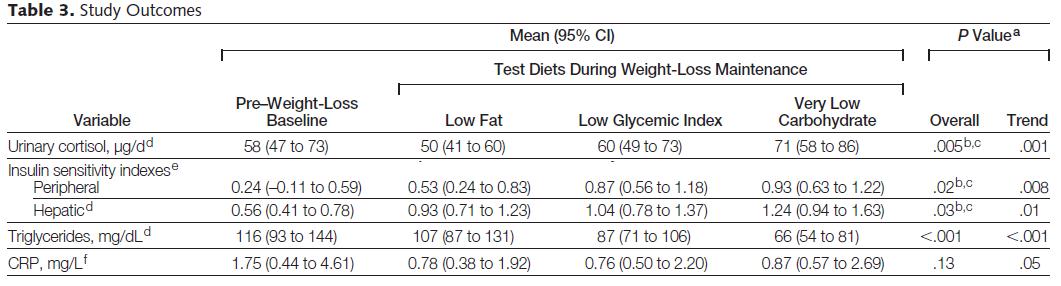

the authors were quick to note urinary cortisol (an anti-inflammatory and stress hormone) and CRP (a marker of systemic inflammation) were highest on low carb, and this could cause insulin resistance. However, I’d note 2 things: 1) CRP declined in ALL groups relative to baseline, but the reduction was less in low carbers compared to the other groups; and 2) CRP was low and within the normal range in all subjects throughout the entire study. But most importantly, hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity improved most in low carbers, in whom CRP and cortisol was the highest.

Similar to the Jakubowicz study (dessert for breakfast), the Ebbeling study was interesting but not groundbreaking; nothing to write home about. Both showed modest benefits for low carb over low fat. The news media haven’t feasted on these studies yet, but when they do, however, I’m sure they’ll disagree. “Weight-loss maintenance” is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, not a simple question to be elucidated by a mere 4-week diet study, even if it’s a three-way crossover. even if it has dark magic.

If you’d like to consult with me, reach out: drlagakos@gmail.com.

Check out my Patreon campaign! Five bucks a month gets you full access and there are many other options. It’s ad-free and you can quit if it sucks 🙂

Affiliate links: Still looking for a pair of hot blue blockers? TrueDark is offering 10% off HEREand Spectra479 is offering 15% off HERE. If you have no idea what I’m talking about, read this then this.

Join Binance and get some cryptoassets or download Honeyminer and get some Bitcoins for free!

20% off some delish stocks and broths from Kettle and Fire HERE.

If you want the benefits of ‘shrooms but don’t like eating them, Real Mushrooms makes great extracts. 10% off with coupon code LAGAKOS. I recommend Lion’s Mane for the brain and Reishi for everything else.

Join Earn.com with this link.