The final horcrux! Empty calories induce a feed-forward loop that promotes over-consumption. … the following evidence is indirect, of course, but very compelling.

Food intake measured by an automated food-selection system: relationship to energy expenditure (Rising, Ravussin, et al., 1992 AJCN)

This study was designed to validate a new technique for measuring food intake; it had nothing at all to do with “empty calories.”

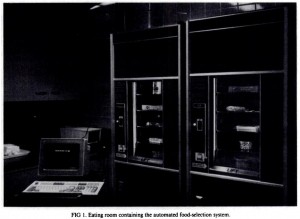

10 lean, healthy young men. During a 4-day run-in period, the amount of calories required to maintain energy balance was measured with extreme precision. Then for 7 whole days, they lived in a metabolic ward and dined from … wait for it … “vending machines.”

The vending machines were loaded with entrees, snacks, and beverages, [sic]: “familiar and preferred foods,” aka a “cafeteria diet.” And I was delighted to see they also published the menu:

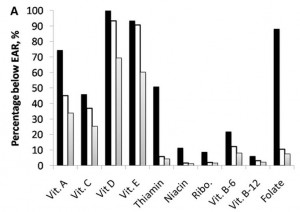

This study fit so perfectly because the Empty Calories series’ singular major thesis is: empty calories promote over-consumption. And this can be tested by examining the two logical extremes: 1) a diet devoid of empty calories is inherently healthier, and any increase in the amount of empty calories consumed is accompanied with a decrease in health outcomes; and 2) eating more empty calories will not be balanced by eating less of something else, because empty calories are nutritionally bankrupt and do not affect satiety proper. And this menu, oh yes, is almost entirely empty calories.

The researchers purposely filled the vending machine with individually packaged processed foods because of their convenience; it’s a very easy way to measure food intake, which was the focus of their study.

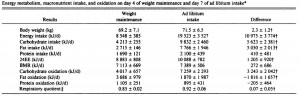

The following figure is absolutely nuts; you couldn’t make this stuff up. like it was mathematically designed to support the Empty Calories credo.

It started immediately on day 1 of “ad libitum intake;” food intake doubled- the food was so nutrient poor that twice as many calories were necessary to satisfy their appetite.

Where did all those excess “empty calories” go? Some (~17%) were spontaneously burned off (increased 24h EE) but most were invested in the infamous negative-yield* calorie savings banks (i.e., adipose). [*you don’t get back more than you invested].

Side note: check the numbers, an overconsumption of 10975 kJ/d = 2622 kcal. For 7 days = 18,353 kcal; which is approximately the amount of energy in 5.2 pounds (2.4 kg) of fat tissue. They gained 2.3 kg, just a hair less than mathematically predicted (so much for spontaneously burning off 17% of the excess). Body composition was not measured, but given the huge increase in carbohydrate intake, I imagine insulin levels were through the roof driving all of the excess energy into fat mass.

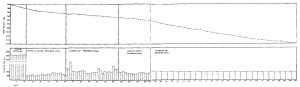

This has been confirmed numerous times. For example, Larsen et al. (1995):

When fed the “cafeteria diet” from vending machines, these women almost doubled their food intake and gained a full pound of fat in under a week. But I digresss.

“And this can be tested by examining the two logical extremes: 1) a diet devoid of empty calories is inherently healthier, and any increase in the amount of empty calories consumed is accompanied with a decrease in health outcomes; and 2) eating more empty calories will not be balanced by eating less of something else, because empty calories are nutritionally bankrupt and do not affect satiety proper.”

The second postulate has been addressed and sufficiently supported by Ravussin’s vending machine study (above). Fortunately for us a study that addressed the first postulate was blogged on previously.

Remember now?

(Hashim and Van Itallie, circa 1965)

When fed a bland yet nutritionally complete diet, obese subjects spontaneously and drastically reduced their food intake, and body weight plummeted for EIGHT STRAIGHT MONTHS. Although this was confirmed a decade later by Cabanac and Rabe (1976), it only indirectly supports the first postulate because it was not real food. But it proves the point that nutrient sufficiency supports satiety, and this can be dissociated from total calorie intake. IOW, if the diet provides the essential nutrition, then the remaining daily energy requirement can be met by burning excess fat mass stored in adipose tissue.

avoid ‘empty calories’ and cash out

calories proper