WRT the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD), I failed to adequately emphasize one major implication of their findings. It is a point that completely and wholly illustrates the disconnect from data, empirical science, and all common sense exhibited by mainstream beliefs in calories and dieting. gravitas

Higher intakes of energy and grain products at 4 years of age are associated with being overweight at 6 years of age (Dubois, Porcherie et al., 2011 Journal of Nutrition)

Divide and conquer

Exhibit A

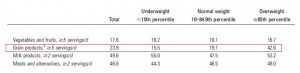

The table above shows the percentage of underweight, normal weight, and overweight children consuming the recommended number of servings for each food group. 15.5% of underweight children, 19.1% of normal weight children, and 42.6% of overweight children meet the recommended ?5 servings of grains per day. Grains comprise [sic]: “breads, pastas, cereals, rice, and other grains”

There is a direct relationship between body weight and the percentage of children consuming ?5 servings of grains per day, i.e., more grains equals greater chance of being overweight.

Exhibit B

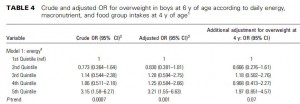

This table shows the odds for being overweight at 6 years of age in increasing quintiles of how many calories consumed daily two years earlier. The crude odds risk (first column) shows a poor relationship between calorie intake at 4 years old and risk of being overweight 2 years later. I say “poor” because the risk is non-significantly lower in the second quintile, higher in the third, lower in the fourth, but much higher in the fifth quintile (3.15x more likely to be overweight for the biggest eaters compared to the littlest eaters). These data are unadjusted and could be confounded by a variety of factors. Thus, the significance level of the trend is high p=0.0007.

The second column is similar to the first, but is adjusted for many known confounders: birth weight, physical activity, mother’s smoking status during pregnancy, annual household income, and number of above normal weight parents. As such, the degree of statistical significance was reduced from 0.0007 to 0.001.

The third and most important column is further adjusted for body weight at 4 years of age, and shows that calorie intake is no longer associated with body weight at 6 years of age. In other words, being overweight at 4 years old predicted being overweight at 6 years old better than calorie intake (and physical activity).

In the authors’ own words [sic]: “The only food group significantly related to overweight was grains.” No association was observed for overweight risk with vegetables and fruits, milk products, or meat and alternatives.

IMHO, the observation that being overweight at 4 years old was the best predictor for being overweight 2 years later is remarkable… body weight status at 4 years old is a more important risk factor than both physical activity and calorie intake. The only ‘controllable’ variable is grains; i.e., you can’t change whether or not your child was overweight at 4 years of age, and physical activity and calorie intake doesn’t matter. But grain consumption seems to matter, and it is something that can be controlled.

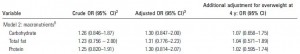

What is it about grains? I don’t know, exactly, but it’s not simply that they’re carbohydrates because elevated carbohydrate intake didn’t increase risk for being overweight.

Exhibit C

“Eating less and moving more” is not the answer. Nutrition matters, not the guidelines.

calories proper