and similar to almond flour, it’s gluten-free and anti-hyperglycemic (i.e., the opposite of white flour).

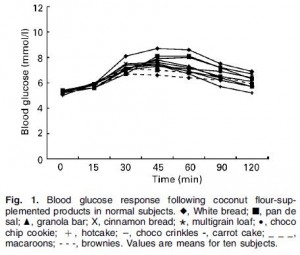

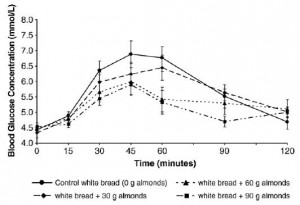

Glycaemic index of different coconut-flour products in normal and diabetic subjects (Trinidad et al., 2003)

In this CROSSOVER study, different doses of coconut flour were incorporated into common test foods to see how they impacted the blood glucose response to said test foods. The total carbohydrate load of each food was 50 grams and to make a long story short, coconut flour dose-dependently reduced the glycemic index.

There’s a lot happening in that figure, but basically the foods with the least coconut flour (e.g., white bread) elicited far greater increases in blood glucose than foods with the most coconut flour (e.g., coconut flour brownies). Mechanistically, this is most likely due to coconut flour’s fiber and/or fat content (both of which slow down glucose absorption and both of which are markedly higher in coconut flour compared than white flour).

Coconut flour: anti-hyperglycemic

Moving on,

the lipid component of coconut flour, coconut oil, is kind-of-amazing in itself.

1) Coconut oil is a perfectly suitable substitute for butter if you’re following a casein-free diet (e.g., GFCF). You don’t need to be a molecular gastronomer or food scientist to try it; refined coconut oil can be used just like butter (“virgin” coconut oil

, on the other hand, retains a strong coconut flavor).

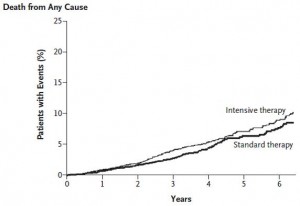

2) Coconut oil is rich in the magical ketogenic medium chain fatty acids (e.g., C12 laurate) and to over-simplify a series of very elegant studies on diet and diabetes (detailed in Diet, diabetes, and death [oh my] [highly recommended reading if you’re into fatty acids, etc.]), coconut oil is remarkably protective against diabetic pathophysiology; a property not shared with lard, corn oil, or shortening.

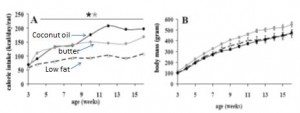

Indirect confirmation of the presence of ketogenic medium chain fatty acids in coconut oil can be seen in this study by Romestaig. Rats fed a diet rich in coconut oil ate more calories but gained less weight than rats fed a high butter or low fat diet:

Coconut oil-fed rats (solid black circles) ate more than the butter group but weighed less. Coconut oil-fed rats ate WAY more than the low fat group but weighed just as much. Nice, huh? Getting back to the point, this is virtually identical to what happens on bona fide ketogenic diets (see Episode 2 of the ketosis series and Ketosis, III), where carbohydrates are kept below 5% of calories (which is phenomenally low, 25 grams on a 2000 kcal diet).

Coconut flour: anti-hyperglycemic

Coconut oil: ketogenic

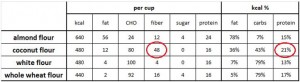

Coconut protein ? … calorie for calorie, coconut flour has more protein than most other flours.

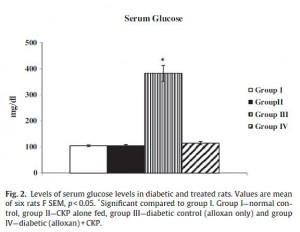

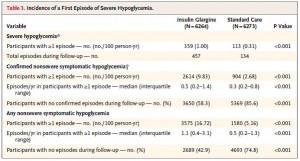

In recent study on diabetic rats, Salil showed that coconut protein completely protected against alloxan-induced diabetes (this study was published in 2011; unlike the earlier studies referenced above, researchers are no longer allowed to give fatal doses of alloxan to rats and count the days until they die. Nowadays they just look at the surrogate marker blood glucose [it goes up very high in diabetes]). Alloxan is a pancreatic toxin which destroys insulin-producing beta cells.

Group 1 (open bar) = controls group. Group II (black bar) = fed coconut protein. Group III (vertical stripes) = diabetic. Group IV (diagonal stripes) = diabetic and fed coconut protein. A diet high in coconut protein made these rats invincible to alloxan… just like coconut oil. Coincidence? (to be continued)

Coconut oil and coconut protein are both present in coconut flour. While it’s not as expensive as almond flour, coconut flour is still pricier than regular white flour. But people love their baked goods, pastas, and breads. If there is ever going to be a way for these foods exit the realm of “empty calories,” the first step is abandoning white flour. Maybe your muffins won’t be so big and fluffy, but neither will your ass.

calories proper