GB Grains blog, take II

The effect of increasing consumption of pulses and wholegrains in obese people: a randomized controlled trial. (Venn et al., 2010 JACN)

I like this study because of its thorough dietary intervention. The researchers provided a lot of the food, had frequent meetings, checkups, and dietary counseling sessions. They even sponsored cooking lessons and supermarket tours! Those are all definitely strengths, in addition to the ultra-long study duration of 18 months. Both groups were advised to eat low fat diets, but the intervention group was specifically instructed to eat more whole grains. To supplement their diets, the intervention group was given rolled oats and rye, wholemeal flour breads, etc., while the control group received cornflakes, cans of fruits & vegetables, refined grain breads, etc.

How’d they do? As seen in figure 1 (below), the diet was followed quite well.

Figure 1. Everybody tried to eat healthier in this study, so whole grains increased in both groups. But it was significantly higher for most of the time in the intervention group. Everybody also ate fewer calories. And since whole grains are both carbohydrates and fibrous, consumption of these increased in both groups, but more so in the intervention group.

To make a long story short, both groups lost approximately equal amounts of weight with the treatment group losing slightly more than control. The interesting thing is that we would have expected these weight losses to be accompanied by all-around improvements in health. But they weren’t (reminiscent of the Orlistat trials). Fasting glucose is a surrogate for insulin sensitivity. Fasting glucose increased in both groups:

Figure 2. Metabolic outcomes.

Both groups lost weight. Dietary carbohydrates are linked with insulin resistance, and although the % of calories from carbohydrates increased in both groups, the absolute amount decreased because of the large reduction in calories. So they were eating fewer grams of carbohydrates and losing weight… So WHY did blood glucose increase? I’d be willing to bet whole grains had something to do with it. Whole grains increased significantly in both groups. There’s something creepy about whole grains, like how every correlation between them and good health is attenuated after adjusting for confounding lifestyle and dietary factors. Healthy people eat whole grains, but whole grains don’t healthify. Possible suspects include lectins and gluten.

Just like DART, the Venn study was a randomized controlled intervention study, which is very powerful study design.

However the Venn study was a weight loss study, which is very different from free-living individuals eating ad libitum in ‘energy balance.’

Enter: the Jiangsu Nutrition Studies. These epidemiological observational studies have been going on for a while and their goal is to identify dietary patterns that are associated with weight gain.

disclaimer: in general, when coming upon a study of “dietary patterns” I turn around and run away. The data are usually so manipulated that they no longer reflect what a person actually eats. I’m making an exception here because Jiangsu demonstrates an interesting point. Briefly, they were able to differentiate “diets devoid of whole grains” from “diets rich in whole grains,” and two other dietary patterns that couldn’t be characterized by their whole grain content.

Vegetable-rich food pattern is related to obesity in China. (Shi et al, 2008 International Journal of Obesity)

Dietary pattern and weight change in a 5-year follow-up among Chinese adults: results from the Jiangsu Nutrition Study. (Shi et al., 2010 British Journal of Nutrition)

They somewhat humorously defined four major dietary patterns:

Divide and conquer.

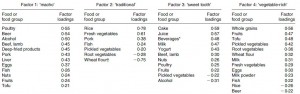

Table 1. Dietary patterns. Focus on the foods with the biggest “Factor loading,” as these are the most important foods that define each pattern. In the traditional diet, for example, presence of rice (0.78) and absence of wheat flour (-0.75) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wheat_flour are the two most important factors that distinguish the traditional dietary pattern. Presence of whole grains (0.56) is what most defines the vegetable-rich pattern. Those are the two I think are of most interest: traditional dietary pattern is defined by an absence of wheat flour, while the vegetable-rich diet is defined by an abundance of whole grains.

In 2002, the food intake data were collected and analyzed. For each dietary pattern, subjects are divided into quartiles based on their adherence to each respective dietary pattern. IOW, every subject is ranked on their adherence to each dietary pattern. For example, you might rank very high for macho, intermediate for vegetable-rich, and low for traditional and sweet tooth. You are ranked by your adherence to each dietary pattern.

To analyze the effect of a dietary pattern on a specific health parameter, investigators compare the prevalence of that parameter outcome across quartiles of each dietary pattern. If there is no association between a specific dietary pattern and the health parameter, it would be similar across quartiles. If, OOTH, the parameter increases or decreases across all 4 quartiles, then there is a correlation.

At baseline (2002) and follow-up (2007), the subjects were weighed. The figure below depicts weight change between 2002 and 2007 and is divided into quartiles of each dietary pattern.

5-year weight change across quartiles of each dietary pattern. Can you spot which two of the four dietary patterns were significantly associated with weight change?

Traditional diet, defined by the absence of wheat flour (top left). People who were the most adherent to the traditional diet (“Q4”), meaning they never touched wheat flour, gained the least amount of weight over those 5 years. Conversely, people who were the least adherent to the traditional diet (“Q1”), i.e., those who ate the most wheat flour, gained the most weight over those 5 years (~2.0 kg).

Vegetable-rich diet, defined by an abundance of whole grains (bottom right). People who were the most adherent to the vegetable-rich diet, meaning they ate plenty of whole grains, gained the most weight over those 5 years (“Q4,” 1.6 kg). Conversely, people who ate the least whole grains gained the least weight over those 5 years (“Q1,” 0.4 kg).

It gets worse.

The prevalence of frank obesity (BMI > 30) according to adherence to the vegetable-rich (high whole grains) diet:

Obesity is far more prevalent among those consuming the most whole grains compared to the least. To make a stretch, people who ate the most whole grains were twice as likely to be obese (bottom row, first [6.9] compared to fourth [15.0] quartile).

Whole grains are associated with frank obesity in the total population, but they are really really associated with obesity in folks between 31 and 45 years of age:

People aged 31-45 with the highest intake of whole grains were 3.66x more likely to be obese than people with the lowest.

The Jiangsu Nutrition studies are observational, but prospective. The Venn study (above) and DART are randomized intervention trials. Obesity (Jiangsu), elevated fasting glucose despite weight loss (Venn), and all-cause mortality (DART)… Collectively, these findings suggest that whole grains should be abandoned, or at least demoted to “consume sparingly.” But their elite status among dietitians and health advocates prohibits this. Divide and conquer?