A randomized pilot trial of a moderate carbohydrate diet compared to a very low carbohydrate diet in overweight or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes (Saslow et al., 2014)

Disclaimer: this study was not ground-breaking; it was confirmation of a phenomenon that is starting to become well-known, and soon to be the status quo. That is, advising an obese diabetic patient to reduce their carb intake consistently produces better results than advising them to follow a low fat, calorie restricted diet.

The two diets:

Moderate carbohydrate diet: 45-50% carbs; 45 grams per meal + three 15 gram snacks = 165 grams per day; low fat, calorie restricted (500 Calorie deficit). Otherwise known as a “low fat diet (LFD).”

In their words: “Active Comparator: American Diabetes Association Diet. Participants in the American Diabetes Association (ADA) diet group will receive standard ADA advice. The diet includes high-fiber foods (such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes), low-fat dairy products, fresh fish, and foods low in saturated fat.”

Very low carbohydrate diet: Ketogenic; <50 grams of carb per day, no calorie restriction, just a goal of blood ketones 0.5 – 3 mM.

In their words: “Experimental: Low Carbohydrate Diet. Participants will be instructed to follow a low carbohydrate diet: carbohydrate intake 10-50 grams a day not including fiber. Foods permitted include: meats, poultry, fish, eggs, cheese, cream, some nuts and seeds, green leafy vegetables, and most other non-starchy vegetables. Because most individuals self-limit caloric intake, no calorie restriction will be recommended.”

Both groups were advised to maintain their usual protein intake.

Results

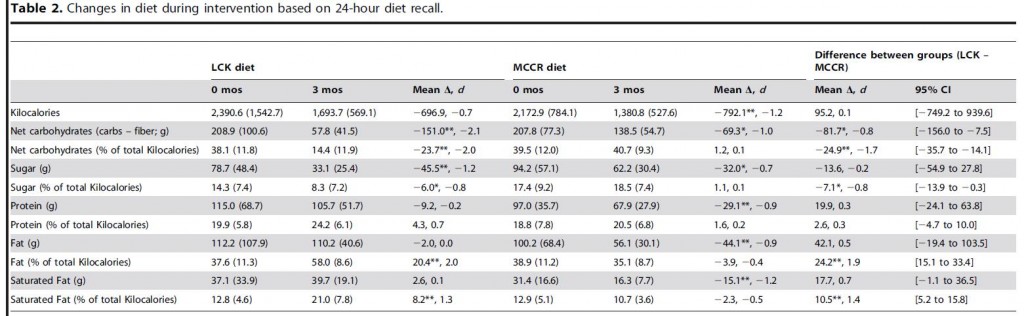

Food intake. Those assigned to LFD went above and beyond the call of duty and reduced Calories by 792. And as expected, those assigned to keto spontaneously reduced intake, by 697 Calories (for the record, that’s a little more than usual). Both groups came pretty close to meeting the other recommendations – carbs on LFD were 139 grams (40% of calories); and 58 grams for the ketogenic dieters. Protein intake declined in the LFD group, which presents a potential confounder as the final differences were pretty big: 106 vs. 68 grams per day (25 vs. 20% of calories).

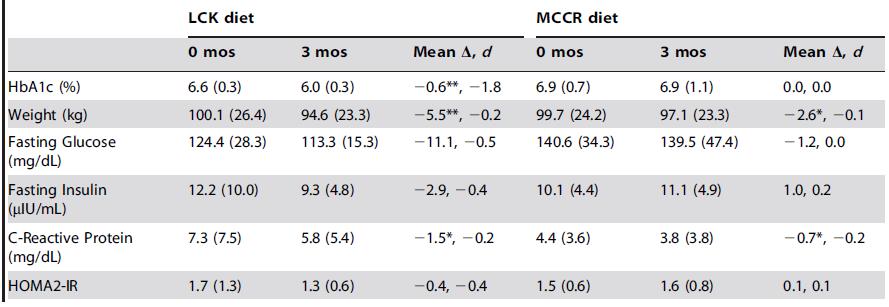

Weight loss: Despite eating fewer calories and undergoing a greater reduction in calorie intake, those assigned to LFD lost less weight than those assigned to the ketogenic diet (5.7 vs. 12.1 lbs).

This wasn’t a metabolic ward study, so dietary information was self-reported via 24-hour dietary recalls. However, most of the ketogenic dieters achieved blood ketones greater than 0.3 mM, which is difficult to do if they were under-reporting carbohydrates (which was their only main instruction).

Body composition: It wasn’t assessed in this study, but more protein and calories in the ketogenic diet strongly suggests better preservation of lean mass… in general, less dietary protein is required to maintain nitrogen balance as total calorie intake increases; the ketogenic diet in this study was higher in both protein and calories.

Other notable changes: CRP, a marker of inflammation, followed body weight. That is, it declined more in the ketogenic dieters. Fasting insulin and glucose also improved more in this group.

just a reminder: the MCCR diet (aka “low fat diet”) is recommended by the American Diabetes Association for the dietary treatment of diabetes. And it’s losing.

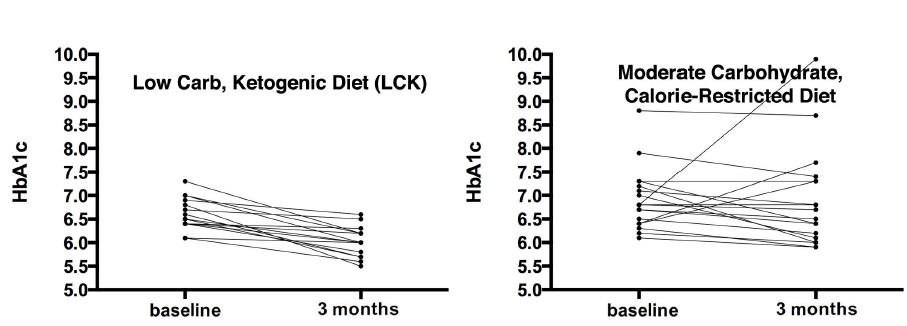

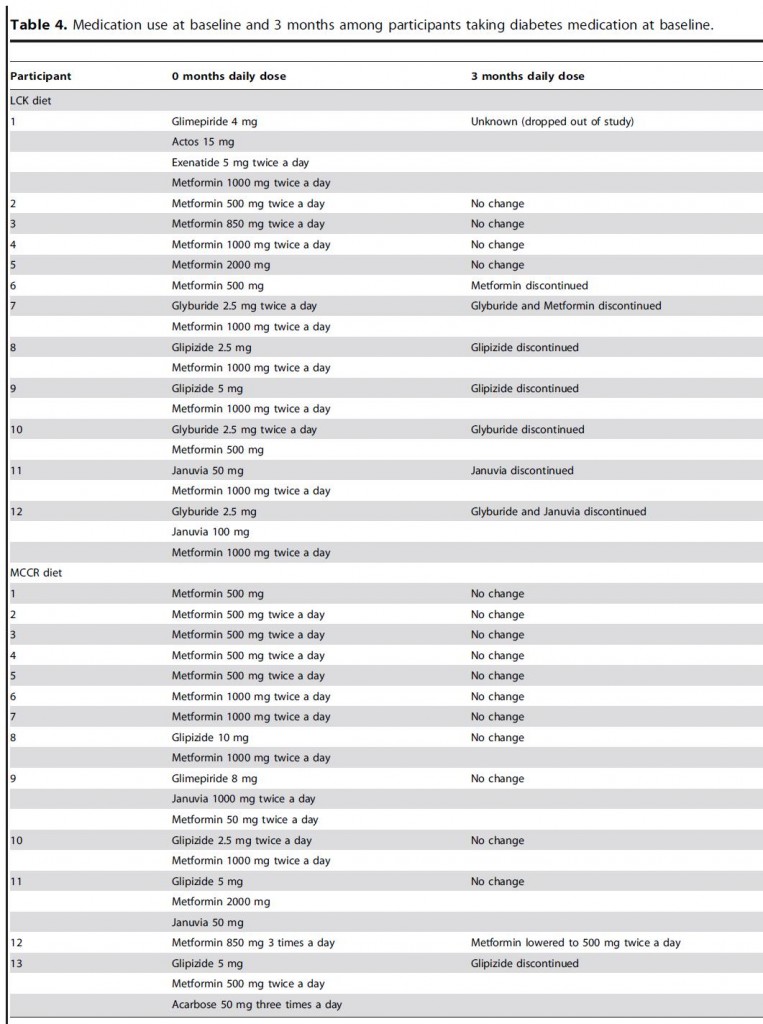

The most important finding of this study, and the one people should be talking about (in my opinion): 7 out of 11 keto dieters (64%) were able to reduce their anti-diabetic medications, whereas only 2 out of 13 low fat dieters did (15%).

What’s most compelling about this finding is: despite reducing their anti-diabetic medications (which should impair glucose homeostasis), markers of blood glucose control still improved in ketogenic dieters.

This isn’t an isolated finding:

Nutrition Disinformation, Part I. (Mediterranean Diet Fail)

How to define a healthy diet. Period. (numerous examples)

Nutrition Disinformation 2.0. (Look AHEAD Study Fail)

Nutrition Disinformation III (William Yancy gets it right!)

The common thread in each of those posts: carbohydrate restriction is numero uno for reducing the need for prescription medications in obese and diabetic patient populations.

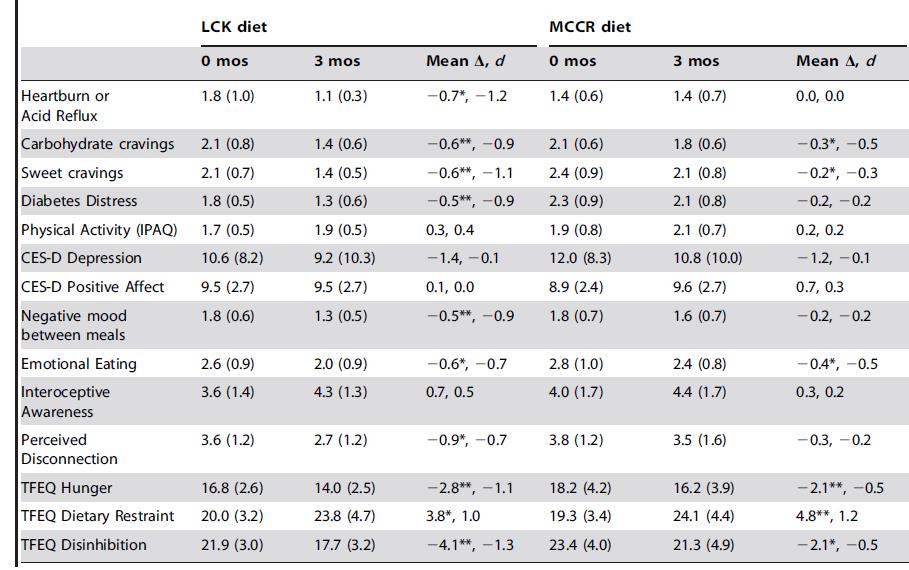

Comprehensive measures of well-being, affect, hunger, and appetite were also reported, I suspect, because the study was partly funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. And interestingly, almost everything got better, even in the keto group. Perhaps this is due to the slow rate of weight loss (~4 lbs/month), reduced hypoglycemic events, or fewer drug-related side effects… then again, interpreting mental health questionnaires isn’t my strongest suit.

Study weakness: small sample size. This is not a statistical weakness, as they had enough power to detect significant differences between the groups; rather, having only a dozen subjects per group doesn’t leave very much room for heterogeneity, individual variability, etc.

Food intake data:

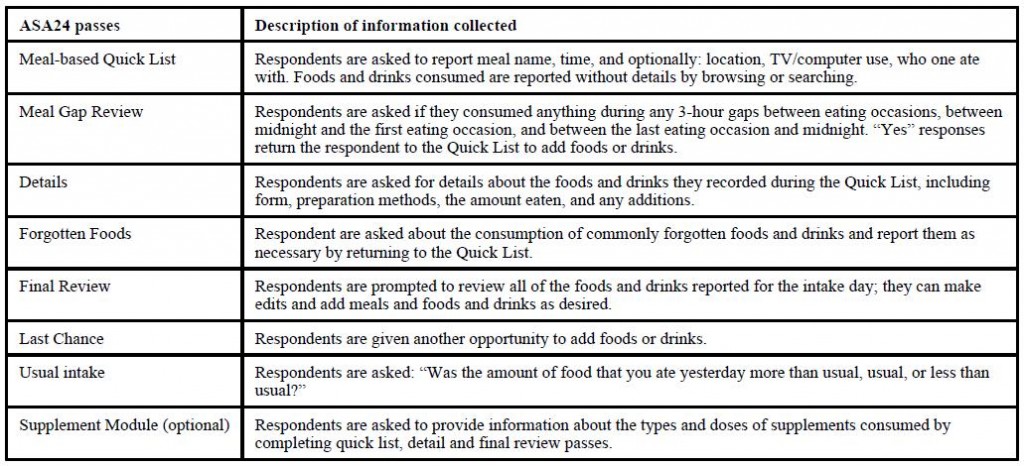

It looks like everyone under-reported, to a degree. That said, for what it’s worth, the 24-hour dietary recall isn’t the worst way to assess food intake. The textbook advantage of this method is that it’s usually very accurate – all of the diet over the past 24 hours is reported, even the unhealthy parts (this is unique to the 24-hour recall; people tell you about the Twinkie they ate yesterday, not the one they ate last week). And it’s far more comprehensive than: what did you eat yesterday, dude?

From Subar et al., 2013

The textbook disadvantage is that it’s only 1 day, which may not fully reflect the usual routine. So it needs to be repeated, which I don’t think happened in this study… but the increase in blood ketones and reduction in triacylglycerols pretty much confirms that the ketogenic dieters were following instructions. And as discussed below, the changes in body weight are also in line for what we would expect if the low fat dieters were following instructions.

Duration: 3 months isn’t too short. This is average, and may even be on the longer side. No, it’s not 5 years-to-life, which is what detractors will say; but in reality, 3 months is pretty good for a diet study. And sure, weight re-gain is going to happen, it nearly always does… the researchers plan on doing 6 and 12-month follow-ups.

Critics of most diet and exercise studies routinely cite small sample sizes, short duration, and sub-par assessment tools. But these things are expensive. If the questions you want answered require big numbers, long duration, and extremely accurate tools, either ask better questions or be smarter.

…

Besides the results about medication usage, another interesting finding was the pseudo-spontaneous reduction in calorie intake in the low carb group. It worked in an ‘ad libitum’ setting, which suggests it can work in real life. I say “pseudo-spontaneous” because they actually, mindfully, reduced carbohydrate intake, but these calories weren’t fully compensated for, leading to an energy deficit. The LFD group actually restricted more calories than they were asked, but they lost less weight. So they were either more severely under-reporting food intake or energy expenditure declined to a greater extent. Either way, it doesn’t bode well.

And lastly, as mentioned above, these finding are not surprising… the authors of this study may have unwittingly “stacked the deck,” in a sense. They specifically included obese, insulin resistant subjects, and Chris Gardner has clearly shown that this characteristic strongly defines who will lose more weight on low carb diets. That is, if the researchers recruited both insulin resistant and [could find enough] insulin sensitive obese participants, and [oddly] assigned the resistant to low carb and the sensitive to low fat, both groups may have been more equally successful. just sayin’