Volumetrics, take II, Op. 64

Greatest dietary predictors of 2-year weight loss success: increased intake of vegetables and meat and reduced intake of empty calories (sugars and starchy carbs).

Proponents of the low-fat diet cite the high energy density of fat (9 kcal/g) relative to carbohydrate (4 kcal/g) and claim you can eat more carbs than fat without exceeding your daily calorie budget: 100 grams of carbs = 400 kcal; 100 grams of fat = 900 kcal. And by extension, you will: 1) feel fuller after a high carb meal; 2) eat fewer calories; and 3) lose weight. Bollocks, bollocks, and bollocks. Diet studies that compare low-fat to low-carb impose strict calorie restrictions on the former and unlimited consumption of the latter.

The “energy density of food” theory is about as valuable for weight loss as “eat less, move more,” and “a calorie is a calorie.”

Fiber and water, the great filler-uppers, have done nothing in the battle of the bulge.

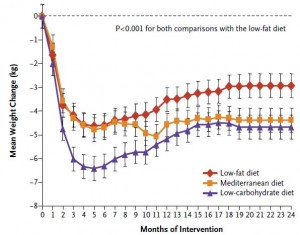

The figure above is from the now famous (or infamous, in certain crowds) Shai study. A manuscript was recently published that tried to figure out which foods were most (or least) associated with successful body weight management at two distinct time points: 1) weight loss at 6 months; and 2) weight maintenance after 2 years.

Effects of changes in the intake of weight of specific food groups on successful body weight loss during a multi-dietary strategy intervention trial (Canfi et al., 2011 JACN)

The reduction in food consumed was ~24% on the low fat diet and ~33% on the low carb diet, despite a similar reduction in calories (~22%) in both groups. The low fat diet was not “more satiating;” both groups were eating the same amount of calories. Yet the low carb dieters lost more weight. But the point of the new study was about which foods were the best predictors of success in all of the groups. Ample information about the dietary intervention, cute food pyramids (see below), and sample meal plans are available in the online supplement.

By and large, the results were similar for weight loss (at 6 months) and weight maintenance (24 months); IOW, whatever helps you lose weight also helps keep it off. But there some interesting differences. For example, increasing vegetable intake assisted weight loss but was less important in the long-term. Conversely, reducing starchy carbs (bread, pasta, cereals and potatoes) was moderately important for weight loss but universally important for maintenance of a reduced body weight. Increased meat intake was one of the best predictors of successful long-term weight loss independent from background diet (it was equally true for low carb and low fat dieters). In other words, increasing vegetable intake can help jumpstart a weight loss diet, but reducing starchy carbs increasing meat intake need to be permanent lifestyle changes.

By and large, the results were similar for weight loss (at 6 months) and weight maintenance (24 months); IOW, whatever helps you lose weight also helps keep it off. But there some interesting differences. For example, increasing vegetable intake assisted weight loss but was less important in the long-term. Conversely, reducing starchy carbs (bread, pasta, cereals and potatoes) was moderately important for weight loss but universally important for maintenance of a reduced body weight. Increased meat intake was one of the best predictors of successful long-term weight loss independent from background diet (it was equally true for low carb and low fat dieters). In other words, increasing vegetable intake can help jumpstart a weight loss diet, but reducing starchy carbs increasing meat intake need to be permanent lifestyle changes.

And surprise surprise, reducing “sweets and cakes” was also a major factor across all diets. With regard to weight loss, reducing sweets and cakes was statistically more important than increasing vegetables. In fact, it was the most important change of all.

In sum, long-term weight loss success includes a diet with more meat and vegetables and fewer empty calories (starchy carbs, sweets and cakes, etc.).