“please stop asking gurus how many carbs you need to optimize health”

An interesting paper came out recently by Zeevi et al. (2015), showing, in part, that we’re all unique snowflakes (in some contexts).

#context

Mini-rant: this study is in line with a lot of my beliefs about individuality in human biology. We don’t know all the mechanisms, but we do know that some people respond better to some interventions than others. We learn a lot from studies on diet, light, sleep, physical activity, etc., but the findings rarely/never apply equally to everyone (and some people experience completely opposite effects; eg, see studies where individual data are reported). LIGHT exposure can improve sleep quality in some but cause agitation in others. Low carb diets can help weight loss in some people but low fat is better for others. Dairy, wheat, protein, the ‘biome, and fibre/resistant starch all fall into this category. Sleep ‘requirements’ vary by person, season, geography, etc., etc… there’s no QED answers in many of these contexts.

anecdote: some people say they’ve never had better blood glucose than when they were having a few servings of beans/legumes per week; others just report bloating & farts (no bueno).

End rant.

Background reading:

- The Atlantic ran a decent piece on this study (certainly more colorful than my take)

- Reddit AMA with some of the people involved in the study

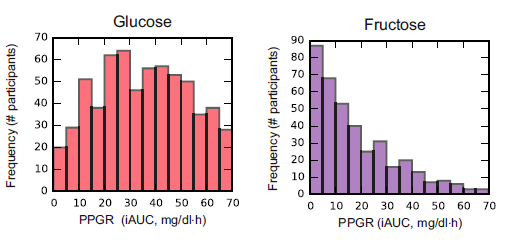

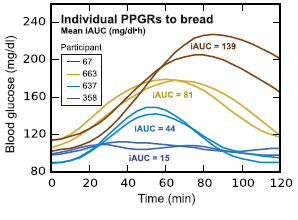

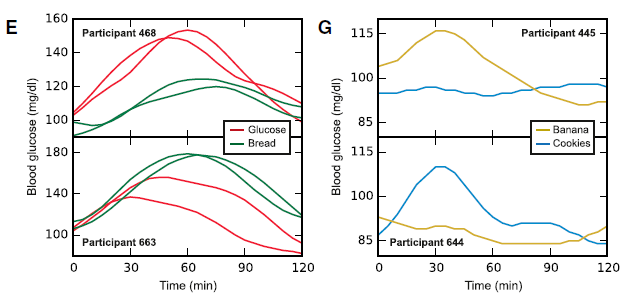

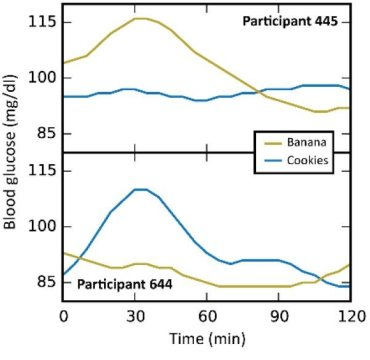

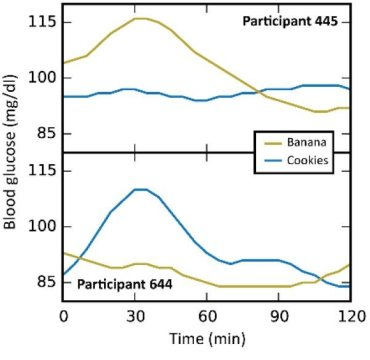

In this particular study (video summary below): they continuously monitored the blood glucose responses in 800 people to all of their meals for a week, including a variety of test meals. Main result: many different responses, even to the same foods! An oversimplified example: some people had smaller relative postprandial glucose excursions after 50g carbohydrate from rice compared to 50g carb from potatoes, and other people responded oppositely. And friggin’ tomatoes?!

Translation: need to move beyond recommending #IIFYM.

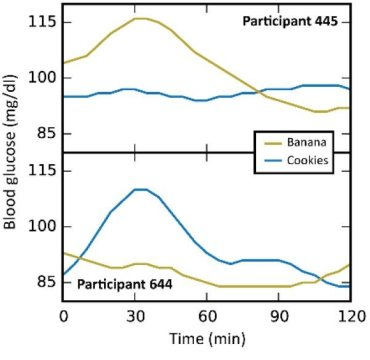

Some foods were universally well-tolerated [in this population] in the context of mixed meals, like quinoa and salmon; other foods did the opposite, like chocolate chip cookies and sushi. And lastly, some foods like cottage cheese and hummus were good for some people but others.

[participant 445 is winning]

[participant 445 is winning]

*In general, I don’t believe in labeling foods as categorically good or bad, which is pretty much confirmed by this study, but some patterns emerged wrt postprandial glucose excursions in this population…

#context

Continue reading →