One way to determine protein requirements is the nitrogen balance technique. If all of the nitrogen from dietary protein intake is equivalent to that lost via feces, urine, and sweat, then one is in nitrogen balance. Growing children and pregnant women are usually in positive nitrogen balance, because much of the nitrogen is being invested in the growth of new tissue. Cachectic cancer patients and sarcopenic elderly may be in negative nitrogen balance, because they’re losing lean mass.

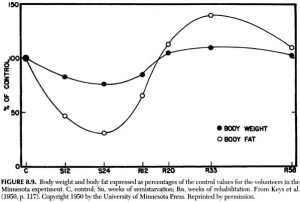

Protein requirements to maintain nitrogen balance are largely dependent on total energy intake. More calories in, less protein needed. For people in negative energy balance (losing weight), this usually means more protein is required else muscle will be wasted.

Exercise lowers, not raises, protein “requirements,” because exercise is a potent anabolic stimulus; it helps preserve nitrogen at any level of dietary protein. That’s not to say more won’t improve functional outcomes; just that it’s not “necessary” to prevent muscle loss.

Need =/= optimization.

Lastly, total grams, not percent of calories, is the most relevant way to talk about protein requirements in the context of nutrient partitioning and body composition. This is just how protein operates.

Part 2. The poor, misunderstood Randle Cycle

“The glucose-sparing effect of fat-derived fuels” …when you’re body starts burning more fat (and fat-derived fuels; ie, ketones), it’s use of glucose declines. Thus, it’s “glucose-sparing” (spares glucose for the brain and obligatory glycolytic tissues, yada yada yada).

During starvation, much of that glucose comes from amino acids from skeletal muscle proteins, so it can also be phrased as: “the muscle-sparing effect of fat-derived fuels,” which is equally biologically relevant, because similar to zeroglycemia, an unabated loss of muscle is incompatible with survival.

That is, in starvation, where the “protein” is skeletal muscle, not dietary (because starvation)… but what about when following a low carb or ketogenic diet – do ketones (fat-derived fuels) exert a muscle-sparing effect in this context?

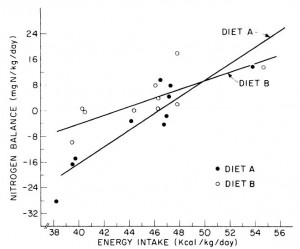

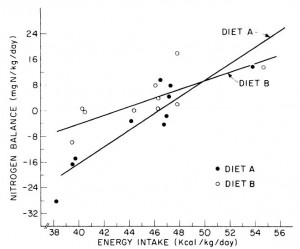

One study compared the impact of two isonitrogenous diets, low carb (Diet A) vs. high carb (Diet B), on nitrogen balance and showed that, except at very high levels of energy intake, nitrogen balance was consistently better on high carb.

However, 51 kcal/kg is the textbook number of kcals “required” for young, moderately active adults. With this understanding, it could be interpreted to mean that nitrogen balance is better with low carb (Diet A) for people in energy balance; and better with high carb (Diet B) if energy deficit.

edit: 51 kcal/kg is for athletes; probably about 20-25% less for non-athletes.

Or not: in another study, a low carb diet promoted better nitrogen retention albeit less weight loss than an isocaloric low fat diet. The low carb group lost slightly more fat mass, which, combined with nitrogen balance data, suggest modestly improved body composition. The differences were small, because this was a “non-ad lib” isocaloric diet study. In the absence of large differences in intake, the most we can expect from such studies are subtle alterations in nutrient partitioning (which are usually difficult to detect).

Cancer cachexia is a condition of severe muscle wasting, and one study set out to determine, more directly, if ketones spared muscle in this context. The study only lasted one week, but I suspect a certain degree of expedited ketoadaptation because: 1) it was very low in carbohydrate; 2) the fat was primarily MCTs ; 3) they supplemented oral ketones; and 4) energy expenditure is elevated in this population. Both the control and ketogenic diets were modestly hypercaloric, but nitrogen balance was more favorably improved by the high carb diet, in contrast to the above studies.

; 3) they supplemented oral ketones; and 4) energy expenditure is elevated in this population. Both the control and ketogenic diets were modestly hypercaloric, but nitrogen balance was more favorably improved by the high carb diet, in contrast to the above studies.

Thus, ketones don’t work in the context of a hypercaloric diet; however, pharmacologically elevating ketones via intravenous infusion in fasting subjects does work (because it’s more like starvation).

The muscle-sparing effect of fat-derived fuels is conceptually and physiologically more relevant to starvation, not nutritional ketosis.

Part 3. Protein “requirements”

Effects of high-protein diets on fat-free mass and muscle protein synthesis following weight loss: a randomized controlled trial (Pasiakos et al., 2013)

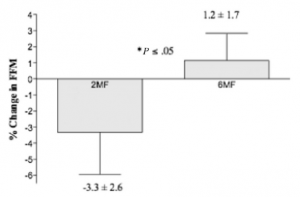

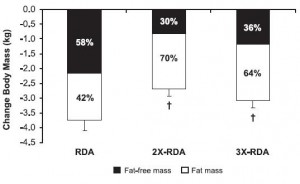

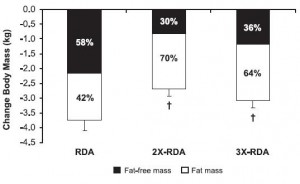

Protein intake was 1x, 2x, or 3x the RDA; fat was 30% of calories, and carbs made up the rest; on a weight maintenance diet and again on 30% calorie restriction (it was technically a 40% energy deficit, because they tried to ramp up energy expenditure with exercise).

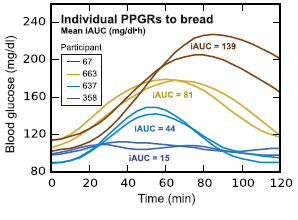

All groups lost weight, but the ratio of fat to muscle loss was significantly higher in the 2x and 3x RDA groups, which amounted to ~120 and 185 grams of protein per day, respectively. The 3x group didn’t fare as well, possibly, because that much protein induces a high degree of satiety – this group ended up consuming significantly fewer calories than the 2x group. So the interplay between energy intake and protein requirements is back on the table: the added energy deficit apparently increased protein requirements to some level above 185 grams per day. Not much, given the small difference in muscle loss, but increased none the less.

Side note: be cautious when interpreting a study about the amount of protein required for xyz endpoint, because such studies usually only measure one of many important markers, and they don’t report absolute changes in size, strength, etc. Also, context matters.

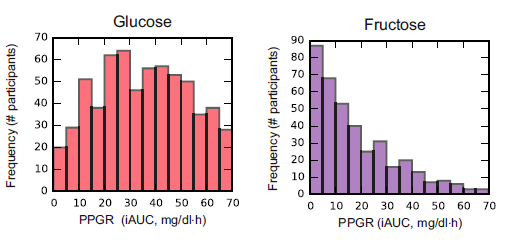

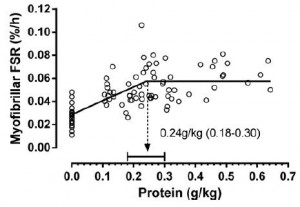

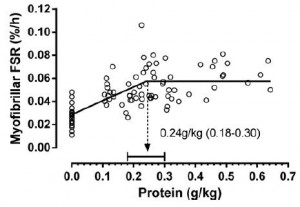

For example, Moore and colleagues (2014) showed that 0.24 g/kg (17 grams for a 70 kg adult) was enough to maximally stimulate myofibrillar fractional synthetic rate (mFSR):

However, in the contexts of three square meals and energy balance (or deficit), 0.72 g/kg (50 g/d) is woefully inadequate. Point being: mFSR (in this case) is only one measurement and shouldn’t be extrapolated to total daily requirements. Perhaps you could eat six 17 g servings in order to fully maximize 24-hour mFSR, or you could realize that going above what saturates mFSR isn’t a bad thing, or wasteful. mFSR is just one of many measurements of muscle protein balance.

My opinion

For those who need exact numbers, hopefully one point I’ve made is that there’s no answer to this question. I’d guess that most people “need” 100+ grams of protein per day (more if losing weight), and 100 grams is probably too much in one sitting. Also, need =/= optimization, and context matters.

Nutritional ketosis doesn’t appear to reduce the amount of dietary protein necessary to maintain lean mass. The muscle-sparing of fat-derived fuels works during starvation; in other contexts, all bets are off.

calories proper